BIBLIOGRAPHY

PART TWO

James Madison

P. 71, P. 73 - Part Two

All mentioned facts are true. Read more about the heated carriage. You can really find a lot of fun stuff in carriage history. Please enjoy the London Steam Carraige, and Horsey Horseless.

P. 75, P. 76 - Flood Comes

There is mention of flooding in Vermont in 1811, though not specifically in Weybridge.

Anna Kingman, Charity’s sister, did tragically die in 1811, leaving behind her husband, Henry Kingman, and seven children: Cyrus, Freeman, Mary Howard, Anna Maria, Lysander, Sally, and Abel. She was 40 years old.

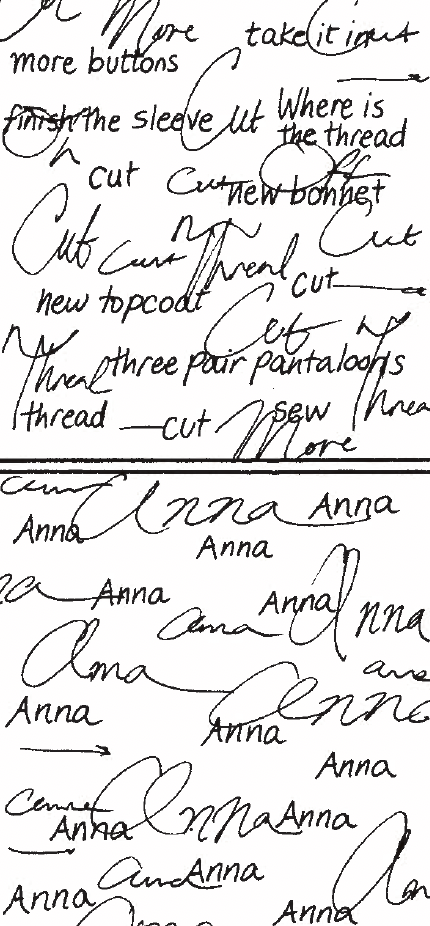

The letter mentioned by Silence is real, I’ve read it and transcribed it at the Henry Sheldon Museum. Here is the full text:

My dear and only sister

Long have I anxiously wished to write to you but could find no opportunity of conveyance but now hearing of one I hasten to address you. I received yours dated April and find you wholly unprepared for the mournful news of which this letter will be the messenger. Oh Charity you know not the pain I feel in telling you of the Death of our sister. She died on Friday the eighth of May after a long illness. She was never in great pain but her faculties seemed to be in a great measure — she was able to walk and ride out till within a fortnight of three weeks of her death.

Little did I think when we last departed that we should never all meet again but In the Midst of life we are in death —- but I have no doubt she is for better off than we. She has laid her aching head and troubled heart in the house appointed for all the beings. Where the wicked cease from troubling. Where the weary one at rest, and I am Left alone without a friend or relation within many miles expecting own family. I kept the letters which you and Sylvia wrote last to Mrs Kingman. They arrived after her Death and I thought it not best to send them to him — with regard to my own family they are all in good health. Mr. Bryant and Philip are at work where they did past seasons when we shall leave this place or where we shall go I know not but nothing I am sure could give me greater pleasure than to live near you. Let Sylvia have a share of this letter if I write another it will be only a repetition of what I have said in this. For I have no power to think upon my other subjects. Give my best love to her and may you both be blessed to accept my gratitude for your unremitting kindness to me, which is all I have to bestow. May God preserve you both a blessing to each other and to me is the Constant prayer of your sister,

S Bryant

Kettle reference

P. 77 - Anna Kingman’s Final Hours

How Anna’s death plays out on this page is imagined, but the pain of her loss is real. Rachel Hope Cleves notes in chapter 15 of Charity and Sylvia that Anna Kingman died of tuberculosis. This disease was also known as consumption. John Green has a wonderful book about the subject called Everything is Tuberculosis.

P. 78 - The Reverend Eli Moody

Very much a real person, and indeed the installed Reverend in Weybridge for a few years. His arrival and departure are known about, but the details are a little fuzzy. His devotion to the gospel and to God is evident in his letters, of which I’ve read many at the HSM. And Sylvia often mentions the power of his sermons. I do not, however, have any idea what he looked like. His characterization is entirely my own.

As Sylvia said in her journal, “Mr Moody preaches too, very affecting” and “Mr Moody convenes with each of us respecting the state of religion in our souls.”

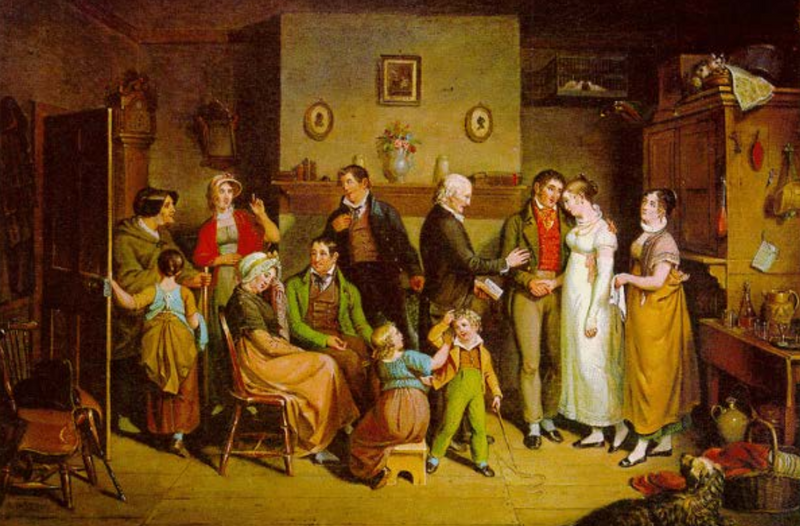

Some crowd reference - Krimmel, 1820

P. 79 - All In Due Time

The details of this vignette were inspired by various passages from Sylvia’s diary:

“We have toiled day and night almost and now”

“Miss Bryant works on Mothers gown.”

“Miss B works and helps me wash windows”

“Bake in oven twice Miss Biron, Miss Carpenter, Miss Jackson come and work for us all day. Miss Kellogg, the former, brings us a new tablecloth and apples. 20 ladies + Mr Moody here to tea. A pain in my head.”

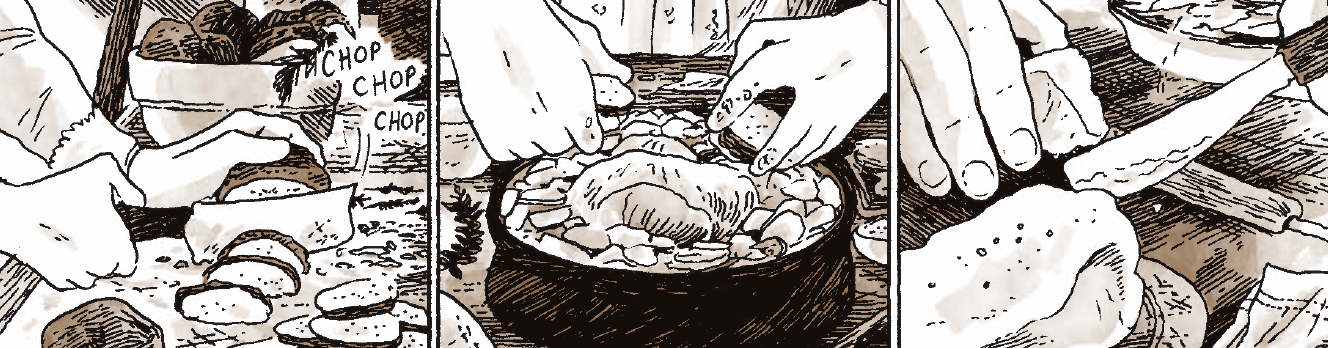

P. 80 - Three Pyes Consumed, Twelve Teas Drunk, One Brandy Spilled

I adored how Sylvia spelled pie in her journal:

“Thursday February 1 very warm Mother chops meat, washes dishes and roasts a turkey, bake mince and pumpkin pyes.”

And there are mentions of brandy:

“Thursday accompany Ms B, sister Ellsworths, have brandy plenty + a good dinner. Oliver + wife + Cyrus have a good visit. Have a roast turkey for dinner.”

And of course, mention of hell:

“Yes, there is room in hell.”

Blake, 1805

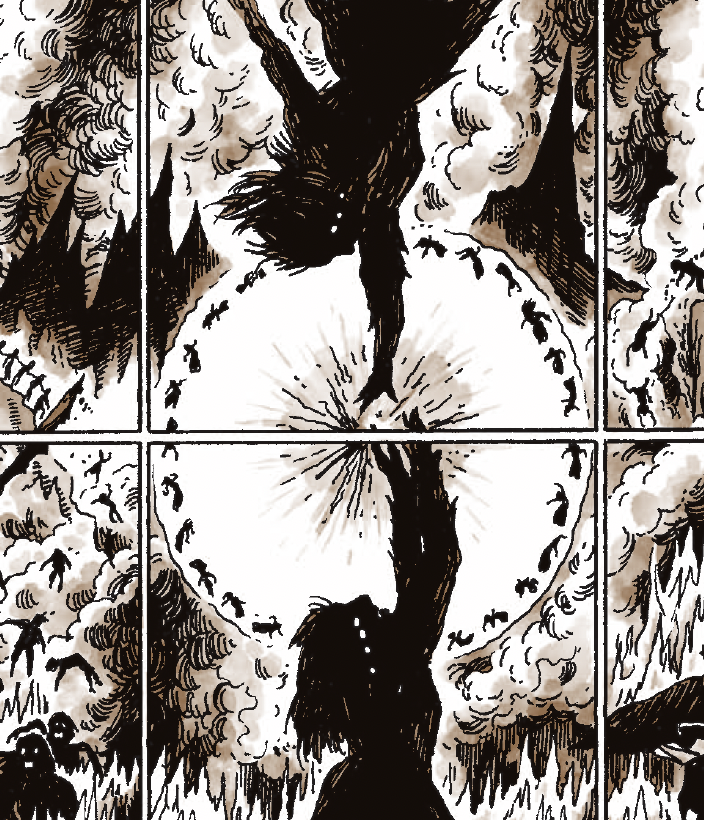

P. 81 - The Hellfire Seen and Feared By Miss Sylvia Drake

I took posing and style inspiration for this page from the wealth of religious art from this era.

Van Eyck, 1440

Portana, 1500s

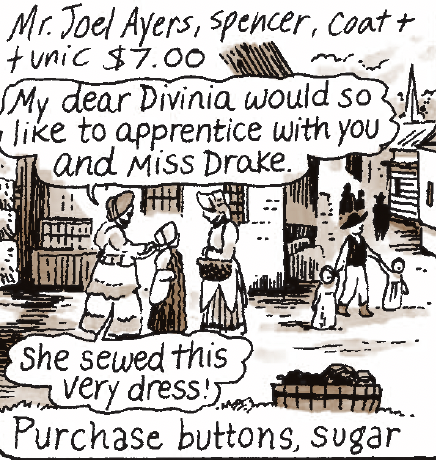

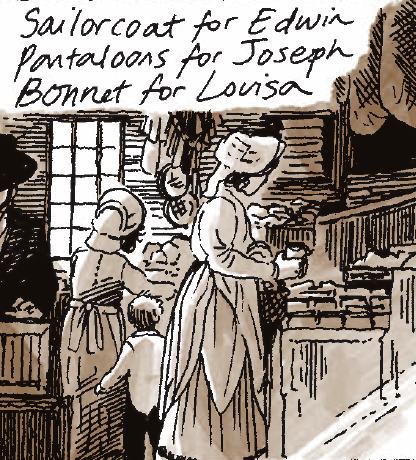

P. 82 - Hellfire or no, Provisions Are Needed

These prices are from receipts and records that have been saved, found at the Henry Sheldon Museum. While I don’t know exact details for how the Moodys and Bryant-Drakes made plans, running into each other would be very likely in a small town. In 1810 the Middlebury population was 2,138.

P. 83 - A Letter, Written On Fresh Paper, to Lydia Richards, From Charity Bryant

This is fabricated, because none of Charity’s letters to Lydia remain. However, a vast amount of Lydia’s letters to Charity can be read at the HSM. I have only been able to read a fraction of them because they are quite long. Based on Lydia’s side of the correspondence, it is clear these women kept in touch for all their lives, and often spoke of their current situations with frankness. So, while the text itself is imagined, the situation behind them is very much real.

18th century tie-on pockets

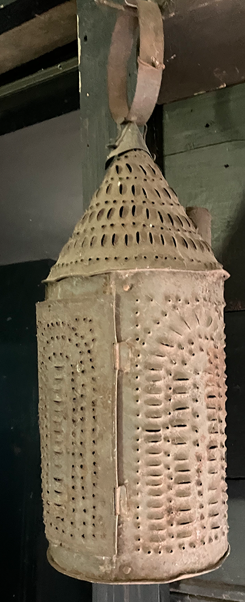

Lantern, Shelburne Museum

Tools, 19th century

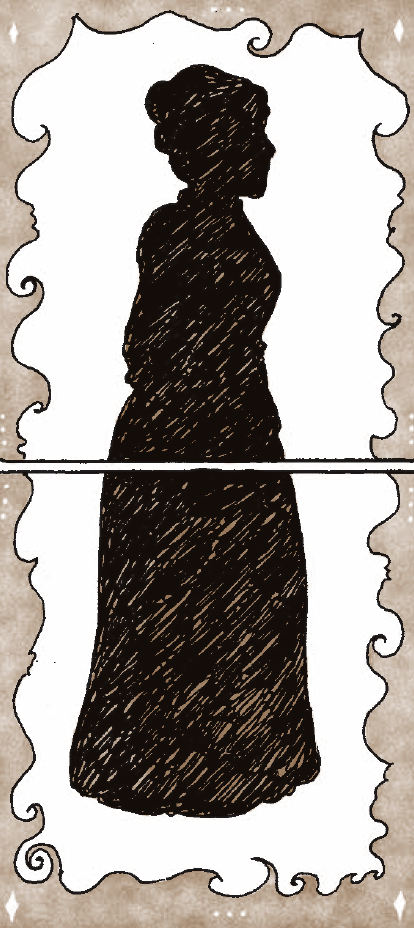

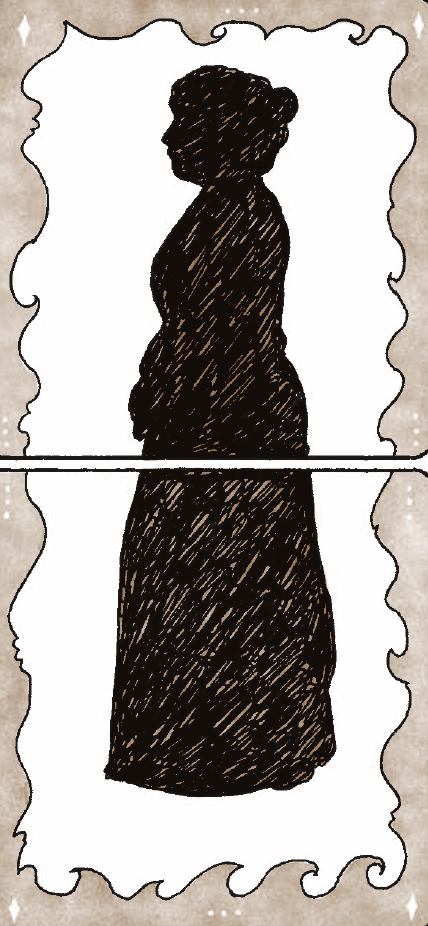

P. 84 - The Only Image to Remain

This is true. The silhouette was made around this time in their lives, and was embellished by one or both of them with their hair and pink paper. Who exactly did the embellishing I don’t know, but Charity had been a tailor for longer than Sylvia, so my guess is that she would’ve done the work.

The silhouette is a sight to behold, and available to see at the HSM.

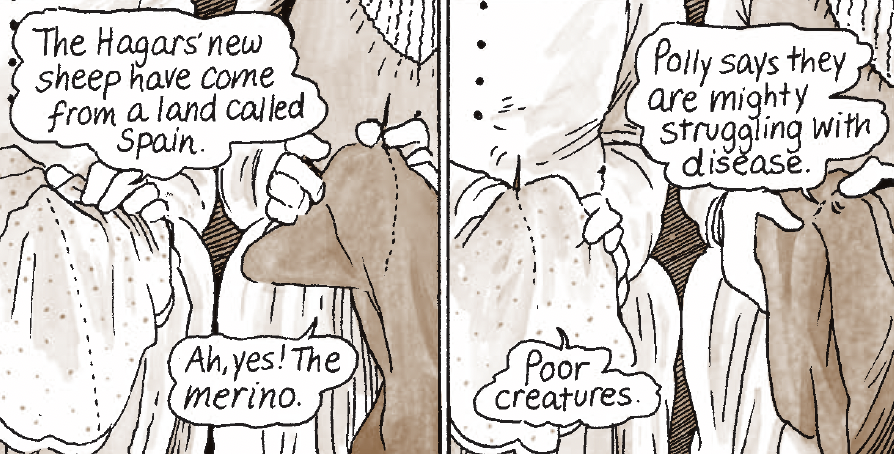

P. 85 - A Flock, Our Flock

Much of this is true. I learned about the history of merino sheep from the VT historical society.

The note about Asaph being involved in brickwork comes from Sylvia’s diary, when she noted “Br Asaph comes with 600 of brick”

Silence, Oliver, and Rhoda all had many children. Rachel Hope Cleves has a very helpful family tree at the start of her book. I do not know which brother exactly suffered the losses mentioned, but Sylvia wrote in her journal of one unnamed brother:

“Dearly beloved brother + son, his only remaining child out of 7”

P. 86 - She Does So Love to Dress Her

For this vignette, and the two that come after it referencing dressing, I used the following lines from Sylvia’s journal:

‘My dear C dresses herself alone for the first time since last July. And says when she comes out dress’d that she made an april fool of me.’

This implies that Sylvia did indeed dress Charity on almost all occasions. And then, of course, this is used to later create the April Fools joke.

Their bed is based off of a historical bed at the Shelburne Museum, pictured here.

P. 87 - The State of the Nation On A Thursday In July When The Moodys Came To Dine

These events are all true. What is less clear is when exactly Charity and Sylvia had dinner with the Moodys, but based on Sylvia’s diaries it happened with a lot of frequency. Quotes from her diary:

“Mr Moody comes over to talk”

“Ms moody comes at 9, mother sews.”

“I attend meeting with Mr Moody.”

“Mr Moody and wife stay to tea.”

“Mr and Mrs Moody dine here.”

The historical events referenced can be read about further - The Chief Tecumseh, The Louisiana slave revolt, James Madison’s presidency, and the War of 1812.

P. 88, 89 - Six Dishes, All Well Seasoned

The friendship between these four is well documented, and all evidence points to their faith being what bound them so closely. See below for text from a letter from Eli Moody to Charity Bryant in 1824, archived at the HSM:

Miss Drake speaks of a destitution of feeling on the subject of religion, and of being absorbed in the cares and concerns of the world. These things, we all know, we ought not to have occasion to speak of. And I hope, my dear sisters, that you, neither of you, now have occasion to speak of them. May I not hope that you are both soaring on the wings of faith and love, and are fast pressing forward in the way of the heavenly —! May I not hope that you let your lights shine, so that all who behold you are constrained to bear witness that you have been with Jesus!

P. 90 - It Was.

This is true. The archive of letters from the Moodys to Charity and Sylvia cover the span of their lives, and their passion for one another is evident. Here is how Eli ends the previously mentioned 1824 letter to Charity:

We shall hope to hear from you again very soon. Mrs Moody unites in love to you both. Please to remember us affectionately, to all our dear friends whom you see. Wishing an interest in your prayers. I am as ever, your friend and brother,

E. Moody

I think I should start ending emails with ‘Wishing an interest in your prayers.’

P. 91 - Wretchedness! Wretchedness!

This is true. I learned about this episode from Sylvia’s journal, where she wrote the following:

“Concert held at Middlebury. A long walk after sweet farm call. Mr Sturdivant - I may well say respecting the old gentleman, Wretchedness! Wretchedness! His mind so completely miserable, that human effort, seems entirely lost. O may I have a heart to pray for him, as long as he is a fit subject for prayer. His temporal circumstances, how deplorable. His bosom friend so simple that she is incapable of affording him comfort + in body or mind. The rest of his household, so peevish, so foolish, so young + toothless, that they are but a grief. I was conducted by his granddaughter thro many a dirty room + at the southern extremity found the old gentleman sitting in his chair, retching with violence, exclaiming lord have mercy on my soul. Weep on! My Soul!”

I give my thanks to Sylvia for writing this down. Stumbling upon this in her journal was extremely exciting after reading seemingly endless passages about the state of religion.

P. 92, P. 93 - We All Must Find A Way

This is somewhat true. Eli Moody often asked Charity for advice in his letters to her, showing a dynamic in their friendship that they trusted one another. Cleves wrote about evidence that Charity requested her letters be destroyed, and also mention of Charity having a journal. Because none of them exist today, it’s fair to say that at least some of Charity’s writings were destroyed. But, this conversation is itself a fabrication. I have no evidence that Charity actually spoke of these things with Eli. I am using the evidence of their friendship to pull these pieces together.

Bucket reference - Shelburne Museum

P. 94, P. 95 - Come Closer: For The Years Will Pass Right Beneath Our Feet

This conversation is a fabrication, but the feelings behind it can be felt in Charity’s writings to Sylvia throughout their life. One poem in 1808, shows evidence of relationship challenges between them:

On the prospect of separation

O shall I still believe

My Sylvia will prove Kind!

That she will ne’er deceive

This heart to her inclin’d

By every gentle tie

That binds the tender heart;

O whether could I fly,

Should she from me depart!

Where could I rest my head

But on her friendly breast,

Short of the silent Dead!

Where all the weary rest,

How could I bear to see

Her from my bosom torn

Another poem written by Charity, from 1847, talks of their feelings and implies challenges faced:

For all your kindness shown

I wish my thanks to give,

And hope to grateful prove

As long as I shall live.

If aught that I have done

Has caus’d you grief of heart

I ask forgiveness Now

E’er we are call’d to part

P. 96 - When All The Storms, An Acrostic

This is real writing of Charity’s, though written in an earlier year than seen here. Her acrostic for Achsah was written back in 1805, and can be found at the HSM:

Alas! Dear girl, what can I say to you -

Can I commend the sympathetic part?

How can I tell you to be Kind and True

Since so much pain attends the feeling heart!

Ah! Yes, my dear, we must be true and kind,

Here is the rest, the trial of the soul;

And tho’ we meet the cold ungratefull mind,

Yet let our kindess every act control.

When all the storms of life are overpast.

As we have cheer’d and rais’d the drooping head;

Reliev’d the heart appress’d by Fortunes Blast!

Divine support will cheer our dying Bed.

Sylvia’s complaints about work and aches are real, and can be seen in her diary:

“People keep calling to get clothes cut, Miss B stand from morning till night.”

‘Bathe Miss C’s arm in hemlock.”

“We have toiled day and night almost”

P. 97, P. 98 - Beckon Me, Oh Please

This is somewhat of a fabrication. I found evidence that Achsah had been a schoolteacher in a letter of Charity’s to her brother Peter that is at the Bureau County Historical Society. But I have no further details about Achsah’s feelings at this time in her life, and can only assume that as a young woman courtship was on her mind.

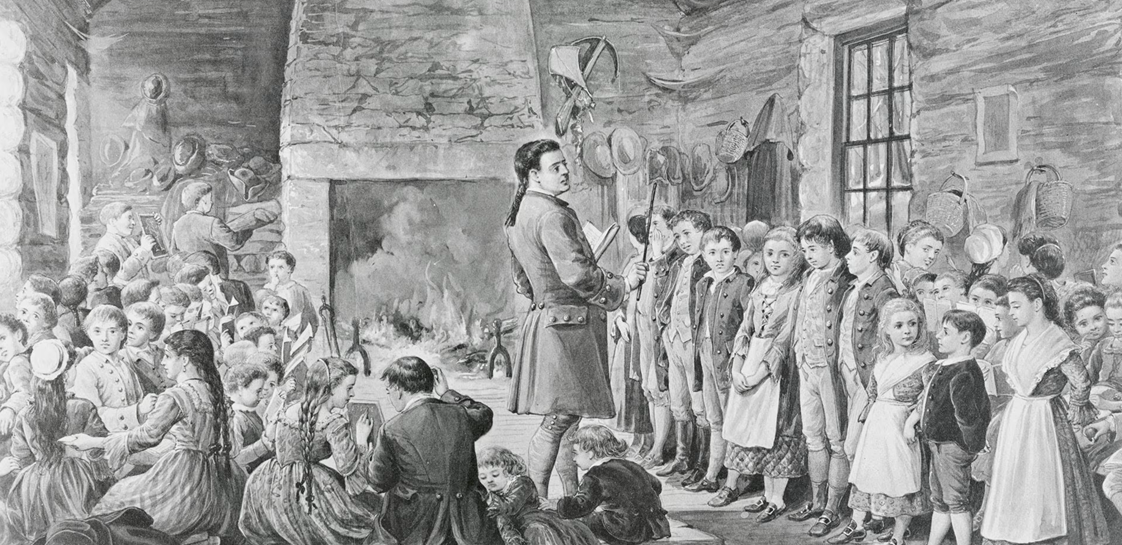

The use of the word ‘cutter’ was common when referring to a horse drawn sleigh. Achsah mentioning it here is inaccurate because the season at the time of this vignette would not allow for the use of sleighs. Whoops! Also included is some general school/environment/children reference.

Colonial schoolroom, 18th century

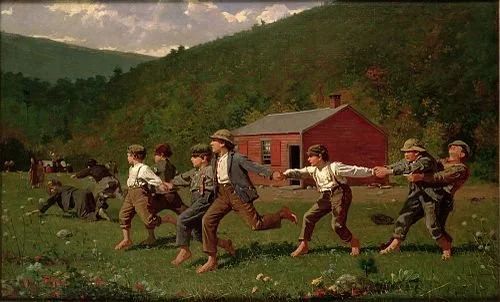

Homer, 1872

Currier, 1871

P. 99 - Can You Discern What Day It May Be?

As referenced earlier, Sylvia wrote of an April Fools joke:

‘My dear C dresses herself alone for the first time since last July. And says when she comes out dress’d that she made an april fool of me.’

Sylvia also often mentioned frustration with worms. Quotes from her diary:

“Destroy the worms on our apple trees.”

“Br A dines here, kill worms, hoe garden.”

“Plant potatoes, kill worms.”

The TV show Dickinson provided a lot of great outfit inspiration.

P. 100, P. 101 - A Comprehensive List

This is fabricated, I don’t have enough details of these women’s lives to know what exactly they loved about each other. But, some details come from Sylvia’s diary, where it is clear she did the majority of the housework:

“very warm Mother chops meat, washes dishes and roasts a turkey, bake mince and pumpkin pyes.”

“Clean the buttery, cupboard, bedchamber, dining room + kitchen, make crackers + bake them, Miss Bryant firing + mending.”

“Sweep the house, clean the candlesticks”

Cleves also notes in her book mention of Charity often missing meeting in chapter 16: “Charity’s religious practice also betrayed tensions. Despite her friendships with the town’s ministers, Charity often missed Sunday meetings.”

On an unrelated note to the history, these pages were a serious relief to me when I got to them. I had to draw this book very quickly, and around page 100 my spirit and energy was really starting to flag. I love the 12 panel grid, but it is brutal from an artistic perspective. Pretty much every page was an intense labor. But these two pages of simple drawings felt like a cool breeze in summer. I remember feeling like I was resetting, and tried to mentally ready myself for 140 more pages of drawing.

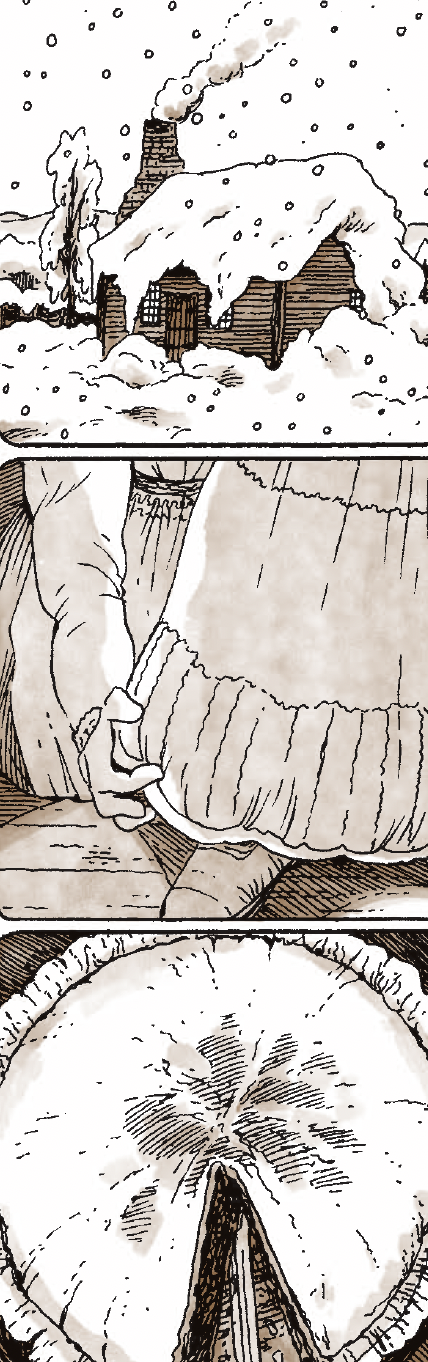

P. 102 - It Is 1816, It Is June (Yes, June), And It Is Snowing (Really, It Is)

This is true. The Year Without Summer was a known historical event, and likely had an impact on Charity and Sylvia’s lives. Vermonters referred to this year as ‘1800 and Froze to Death.’ 6 inches of snow really fell in that month.

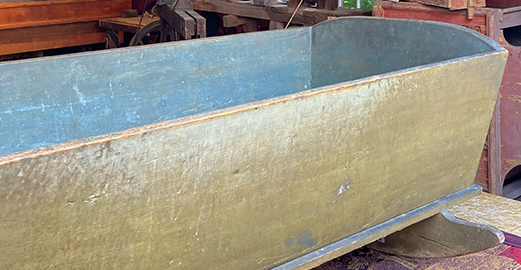

P. 103 - The Cradle, Made By Polly’s Dear Husband, For Their Comfort In Hard Times

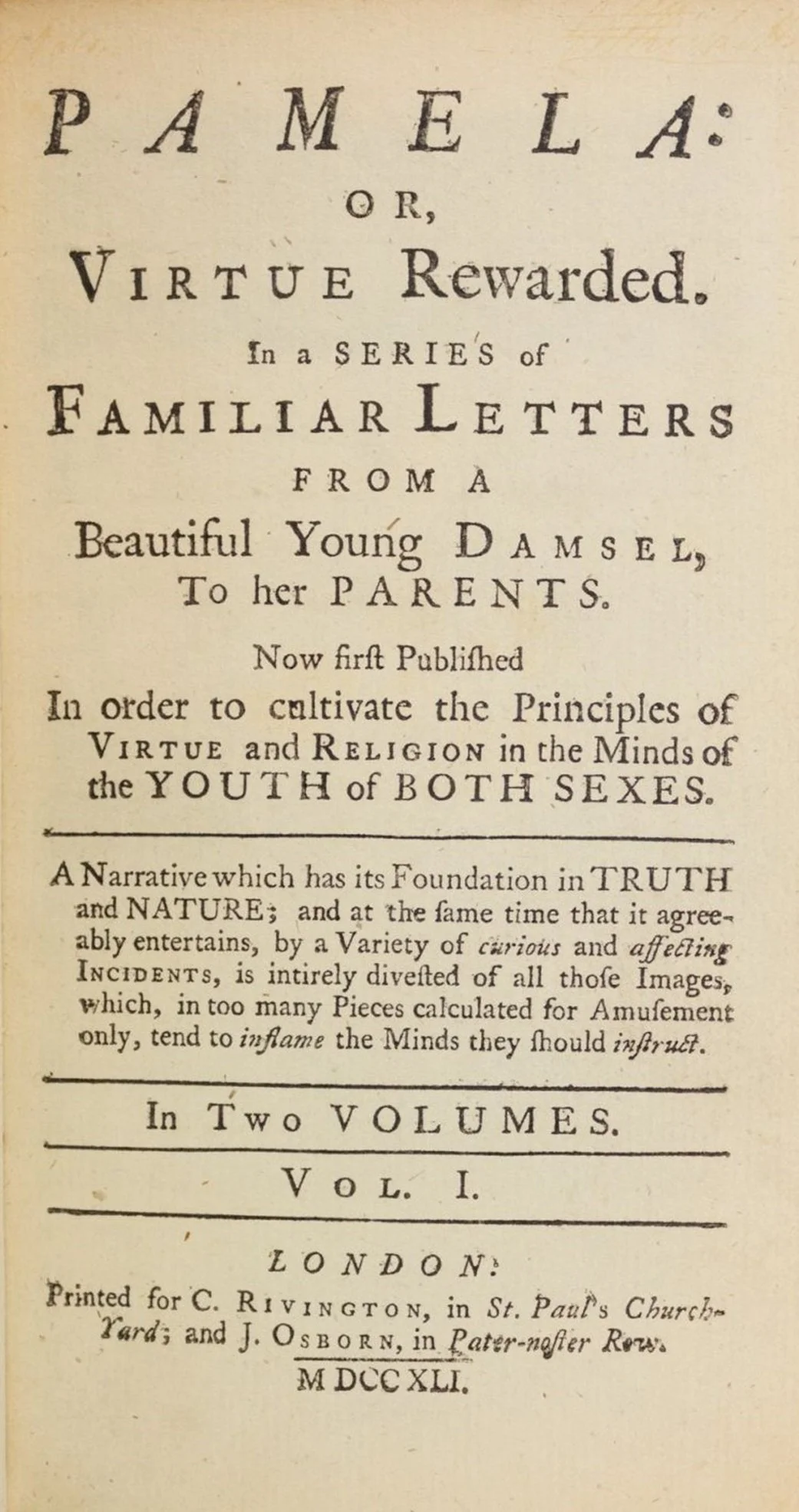

The cradle is real, and remains at the HSM. Cleves notes in chapter 18, as does the archivist who I worked with, Eva Garcelon-Hart, that the cradle was made by Asaph Hayward, Polly’s husband. He was not named in this book because I was concerned about having two Asaph’s in the story. I had, of course, never heard of rocking your lover in a cradle to ease her pains until I began working on this book. But imagine my surprise when I came across this article in the midst of all of this. Cradles were a thing!

Charity is reading an excerpt from Pamela by Samuel Richardson, which Rachel Hope references as a book that Sylvia and Charity read. It was a very popular book in their lifetime, and you can still get a copy of it today. I read it while I was doing my initial research for this book and the tone of it was very inspirational for the dialogue throughout the book.

P. 104 - The Ceaseless Cold

This is true. It was ceaseless, and they lived on. It is hundreds of years later but as I sit and write this bibliography the cold and snow and wind outside my window in this tiny town in central Vermont is, in a word, ceaseless. Some things never change.

P. 105 - A Poem Written While Miss Drake Ails

This is a real acrostic poem written by Charity, for Sylvia. But, it was actually written much earlier, in 1807. This is a consistent problem - I ddin’t have materials from their whole life span, but instead I had concetraed times where there was a lot of writing. Most of Charity’s writing that exists is from her young adulthood. For Sylvia, more exists from her middle age. I needed to try and stitch it all together to make it cohesive, but it meant fabricating quite a few dates and presenting writing in different years from when it was actually written.

P. 106 - The Funds! The Funds!

This is somewhat true. Charity and Sylvia did expand there house at some point in these years, and Cleves explores their economic standing in a tumultuous time in America. She describes that their tailoring business did often keep them in better financial standing compared to their neighbors.

But as always, the conversation is imagined.

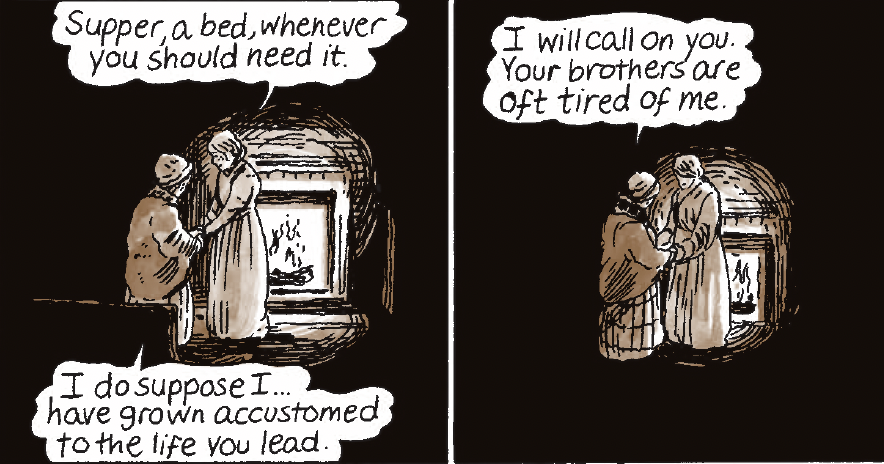

P. 107, P. 108 - Gather, For Times Remain Hard

This is mostly fabricated. I have no evidence that Asaph ever lost his temper at Achsah. The evidence I do have is that at this point in their lives the family was massive. Every Drake sibling had a large family, except for Charity and Sylvia, and dining with family and friends in the community was common. In Sylvia’s journal she writes, “At sister Sopeks, dine on trout, sallad, biscuit, pound cake + custard pye.” There is also some truth to the idea that Sylvia’s mother became accustomed to her atypical lifestyle. She stayed with Charity and Sylvia quite a lot, which sadly didn’t make it into the book for lack of space. From Sylvia’s journal:

“Mother sews on the cradle bedsick.”

“Mother washes dishes, knits.”

“Miss Bryant works on Mothers gown”

The actual tensions in the Drake family will never be known. I can only assume that with such a large family, and in a life that was arguably a difficult one in a subsistence economy, that tensions would occasionally arise. This vignette was my way of expressing these ideas.

The mentions of the aurora are real, and there are records of them being seen in Vermont in this era. The mentions of Emma Willard are also accurate. She was an important figure in the field of education for women.

P. 109 - How The People of Weybridge Continue

Most of these details are fabricated but depict an overall truth. One detail that is actually true is that a girl brought milk to Charity and Sylvia’s house each day, as recorded by Ida Washington in her writing on Weybridge.

Illness was extremely common. In a letter from Charity to her brother Peter in 1813 she mentions a plague:

Every disorder prevails among us, and the shafts of Death fly thick around us, since I wrote last. There has been twelve deaths in this small town and many sick and brought, as it were, to the borders of the grave. Two men now lie dead in this place. Mr David Goodall and Stoughton Dickinson, esq… He was at a store in Middlebury, speaking of the prevailing disorder (which our physicians term the plague) He observ’d that he thot it very contagious and had been very careful about going where it was.

It is also well understood that life in the 1800s was characterized by a strong sense of community. Charity and Sylvia, and the people of Weybridge, would not have been able to live in this time without help from their neighbors. In just one passage in Sylvia’s journal she mentions multiple forms of help:

“Ride in Mr Brewsters cutter.”

“Mother chops meat.”

“16 come to assist in chopping our wood. Some at 3, some at 5.”

And of course, resources were often traded and gifted: “E brings us milk and eggs and I give him a meal. Mr N gives us bacon. Sister sends us a box of sugar by Miss Pratt. Hear of the death of Mr Tudor.”

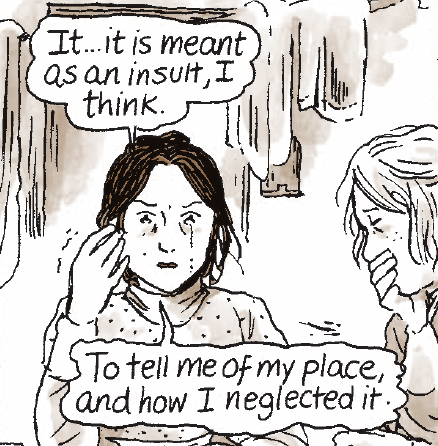

P. 110 - It is August, The Mail Comes

This is true. Charity’s father and stepmother both died in 1816, and Cleves describes in chapter 15 the state of his will, and how the room left to Charity was likely a slight.

P. 111 - If Time is Limited, Then Creation Must Not Wait

These words were actually written by Charity, but in a different year, in 1800. The poem itself is quite long, here is an excerpt:

HE by whose breath all Nature breathes,

Lord feel his vital sway,

Spoke man to life, and give him hope,

An unextinguish’d ray!

Place’d in his breats a strong desire

And an immortal soul.

To prompt him upward to the sky

Where endless pleasures roll

But how revers’d our Mothers gifts!

How in confusion hurl’d!

When we presume to hope for bliss

Within this wretched World!

Yet happiness is all we seek

Our beings end and aim.

Tho various are the ways pursu’d

The object is the same.

Bent on the world how many press

The fugitive to find

But worlds of wealth can ne’er produce

Sweet peace within the mind.

P. 112 - Write Faster, Work Longer, Pray Louder

This is true. They wrote, they prayed, they worked, and they likely had sex.

P. 113 - The Brilliant And Daring Eli Moody

This is fabricated. I have no evidence that Eli Moody mentioned politics in his sermons. What is known is that Middlebury, right near them, was a hub for abolition.

It was likely a topic of conversation and thought.

I do not have evidence that Charity and Sylvia read Emma by Jane Austen, but I wanted to nod to it because it is a book that I think many young people today will recognize, and it was published in their lifetime in 1815.

More outfit inspiration from the tv show Dickinson

P. 114 - Return, Return, Return

Cleves writes in chapter 16 of the ‘remarkable authority that they held within their community of faith,’ and also that Sylvia ‘in later years…led the Weybridge Sunday school, training children to memorize the Bible verse by verse’ in chapter 10.

I discovered the name Electa in Sylvia’s diary and felt the need to use it, it’s such a great name. Another name I came across was Thankful, and I wish I had included it somewhere.

Visually I was consistently surprised by how dark historic homes are. It makes sense when you think about it, of course. It was fun to layer in a lot of shadows in certain scenes to try to recreate the darkness of their home.

19th-century log cabin

P. 115, P. 116 - Hurry, Hurry, Hurry

This is fabricated. Achsah, in reality, died a much slower death. She did truly die young - dying at 25, but her illness lasted for many months as she slowly degraded. Cleves notes, and I agree, that Achsah’s death deeply affected Charity and Sylvia. In chapter 15 Cleves writes:

“Achsah died the following spring at the age of twenty-five. Her aunts mourned her loss to the end of their days. Charity described Achsah’s death in her brief 1844 memoir. Achsah, she wrote, had ‘gradually sunk under the power of that fatal Disease, Consumption, untill May 1818 when much lamented she bid her Friends a final farewell!’ Charity used more words to describe Achsah’s end than the deaths of her sister Anna Kingman in 1811, her father, Philip, in 1816, or her brother Peter Bryant in 1820. Achsah’s death was the only loss on Sylvia’s side of the family that she noted at all; it still carried a sting thirty years after the fact.”

P. 117 - Do Not, Do Not, Do Not

I chose to speed up Achsah’s death for a few reasons. First, it had a little more narrative energy. The shock of her loss, I think, can be felt a little more intensely. And sudden death was very common in this time period. I also chose to speed it up to have more time celebrating Achsah’s life. Had I written her illness in as a years long affair, it would’ve meant that the previous vignettes about Achsah would’ve shown her listless and struggling. Which, to be fair, was the truth of her final year. But descriptions of Achsah maintain that she was lively and smart, and I wanted to emphasize that before her death. I like to think that if Achsah could see this portrayal she would appreciate my choice.

P. 118 - She Was Twenty And Two And Three Months

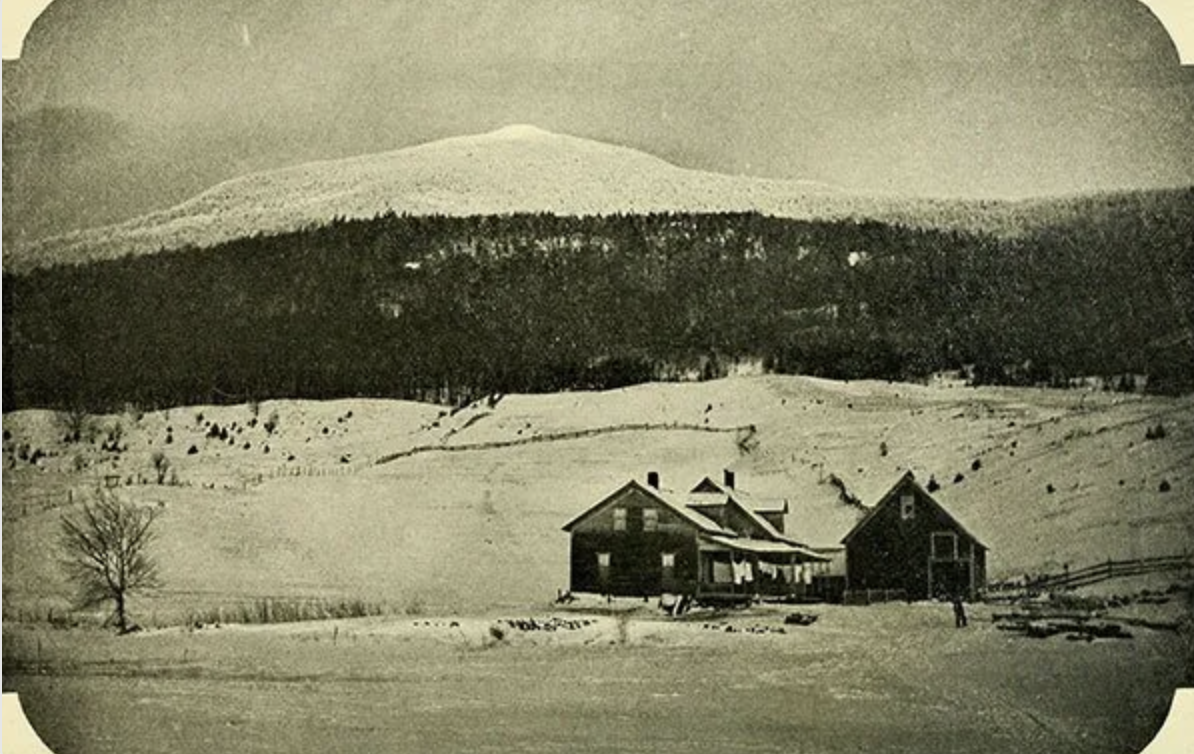

This age is fabricated to match the timeline of the story. Achsah was actually twenty and five and three months. She is buried at the Weybridge cemetery, pictured below, near where Charity and Sylvia were laid to rest.

P. 119, 120 - A Poem, Written by William Cullen Bryant, Charity Bryant’s Nephew

This is a real poem, written in 1818, the year Achsah truly died. Read the full text here.

P. 121 - It is Wish’d She Would Live Again, But Years Pass And She Does Not

These images were inspired by Sylvia’s journal. Mentions of going to Middlebury, of tailoring, of spring, of cooking.

Thompson

Steele

P. 122 - To Build Is To Survive

The actual layout and size of Charity and Sylvia’s house, post renovation, is not known. Here is the evidence I have from Sylvia’s journal as to its scope:

“moves the stove, cleans it, clean the pipe. She puts on lamb black + grease.

Miss B and I clean out the porch + sweep the woodhouse.

cleaning the lower part of the house.

Paints our new cupboard, fixes the curtains + our new table. We move the old one into the woodhouse yesterday.

clean the chambers, Miss B washes the windows, we take up the sage and hyssiop and set it out, trim the currant bushes.

wash 5 flannel sheets, 5 flannel shimes, 1 waist + 6 pairs of stockings, 13 towels, 3 table clothes, 3 pairs of pillow cases, 3 aprons, chiefs, 1 night gown. Clean the buttery, cupboard, bedchamber, dining room + kitchen, make crackers + bake them, Miss Bryant firing + mending

cleans the pictures and the looking glass, mend the table. Miss B and I clean all the lower rooms, pick currants and peas, knead bread and biscuits.

Bubles and trunk

Bedstead + curtains

6 dining chairs

4 kitchen chairs

1 cutting table

1 long table

4 men work for us. Mr S + D digging cellar.

2 women + 8 men work for us.

I go to Mdy with mrs Hr get nails, rum, tea, knives

2 at work on the frame

6 men at work on the frame + roof… our stove pipe falls

5 men at work on the house they board + shingle it

Mr Marshall to begin stoning the cellar… finishes stoning the cellar and making the steps. Esq Kellogg brings us boards. Mr Foster puts up the woodhouse door.

Go to Mdy with Mr Foster, pay almost 3 dollars at Dr Hookers for paint, medicine, almost 3 at Mr Chapmans for nails. 3.64. Mr H 5.70 at Mr Wheelock for glass, crackers + —--

Mr Brewster comes in the morning to make mortar

Mr L + Edwin finishes the outside of the home.

Br Asaph comes with 600 of brick, begin… prime windows. Mr L at work here. Capt W, Mr Marshall, Edwin making pavements. Go to Capt W, wash glass.

Mr L fits + sets 3, 12 light windows in the evening. I carry old plastering.

Mr Brewster brings us 2 loads of boards. Mr Bigelow our cistern.

My dear C accompanies Mr Hr to Mdy purchases glass, nails, Brass door handles, screws, paint brush.

Lauren Drame comes and digs a place + puts down our Cistern. Mr L helps him, draws the water + battens down the clay.

Finish painting the working room, second time paint the clothesroom. Ms Bryant white washes.

Sweep, scald bedstead, hoe in the garden. Take a view of our mansion + garden.”

P. 123, P. 124, P. 125 - A Visitor, Unexpected

This scene is somewhat fabricated. It is inspired by a very interesting and brief part of Sylvia’s diary. It was just two sentences, but it created this whole scene for me:

Sister Louisa stay all night. A sister indeed not in name only.