BIBLIOGRAPHY PART FOUR

P. 153, P. 155 - Part Four

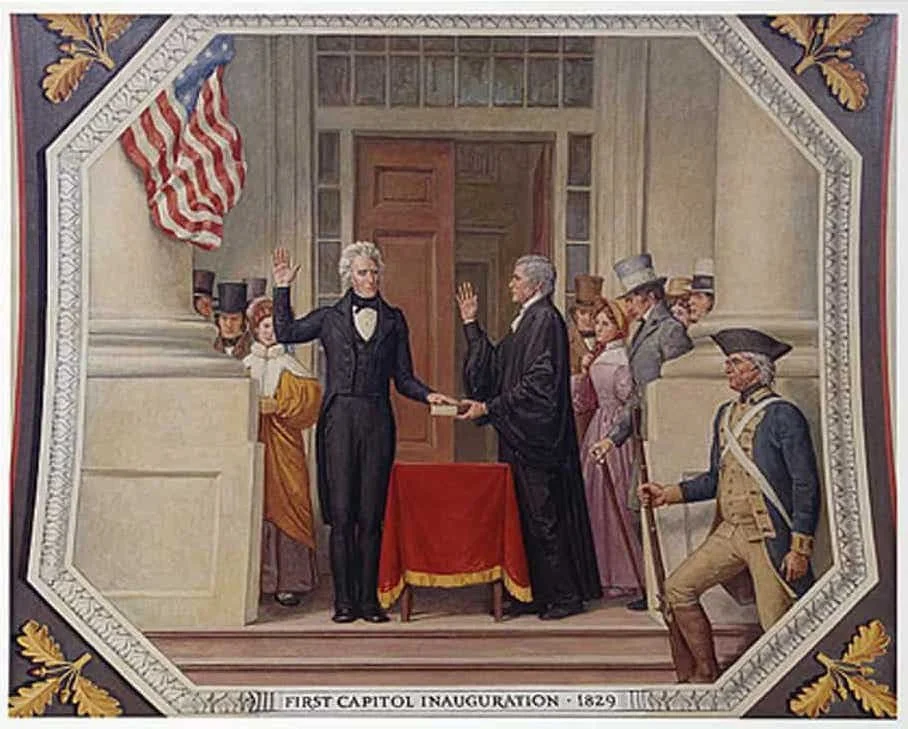

Andrew Jackson was a complex President, and in my opinion, a pretty terrible person. There are many who are not shy of facing his legacy in America.

Also mentioned on this page - The history of Burlington, the lawnmower, so many sheep in Vermont, and the continued practice of Slavery.

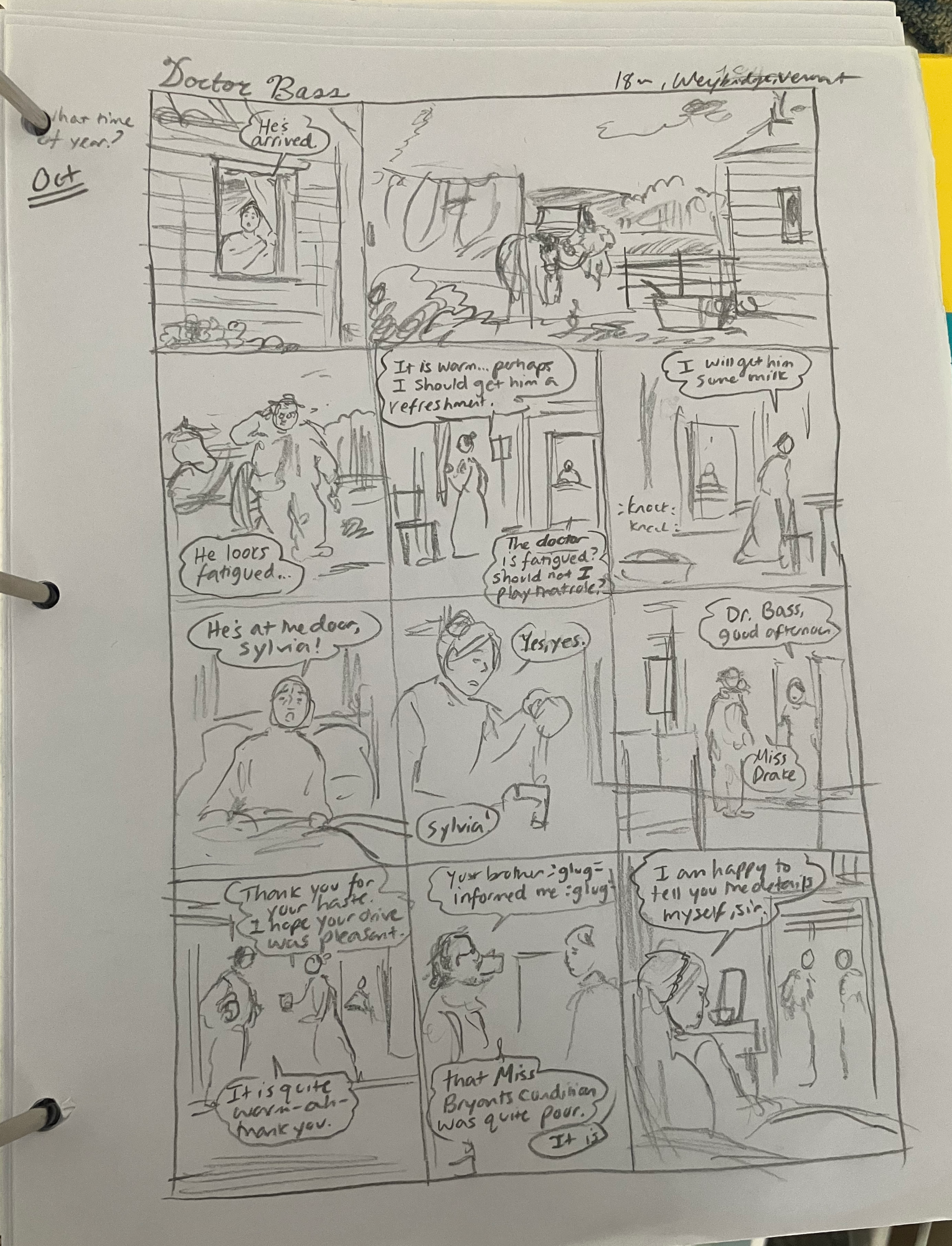

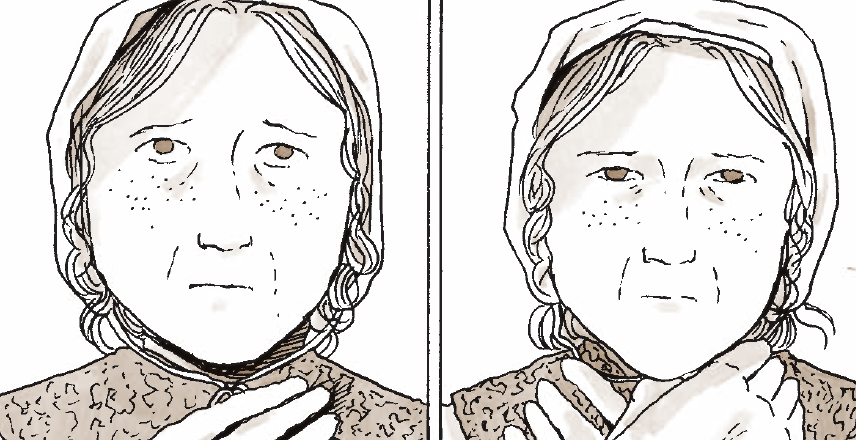

P. 159 - Dr. Shaw Arrives

Charity mentions in a letter at the Henry Sheldon Museum that a Doctor gave her a very bad prognosis and did not expect her to live. It was not actually Dr. Shaw, it was a different doctor, but because Dr. Shaw had been mentioned previously I incorporated him again. Much information remains about Charity’s health, and it is explored at length in Rachel Hope Cleves book in chapter 18, The Cute of Her I Love.

Also of interest - in the original draft of this book, this scene was originally page one. I liked the idea of starting out the story with this dramatic profession from the Doctor, and then jumping back in time to the start of their relationship. Of course, this ultimately changed, and for good reason, but as I was writing this bibliography I remembered the early version!

P. 160 - Our Home, Our Dwelling, Our Life

Sylvia consistently refers to their home as a ‘dwelling’ in her journal.

Their renovated and expanded home is based off of yet another historical home maintained at the Shelburne musem. I wasn’t able to see the upstairs, but the downstairs interior and exterior were direct sources for Charity and Sylvia’s house.

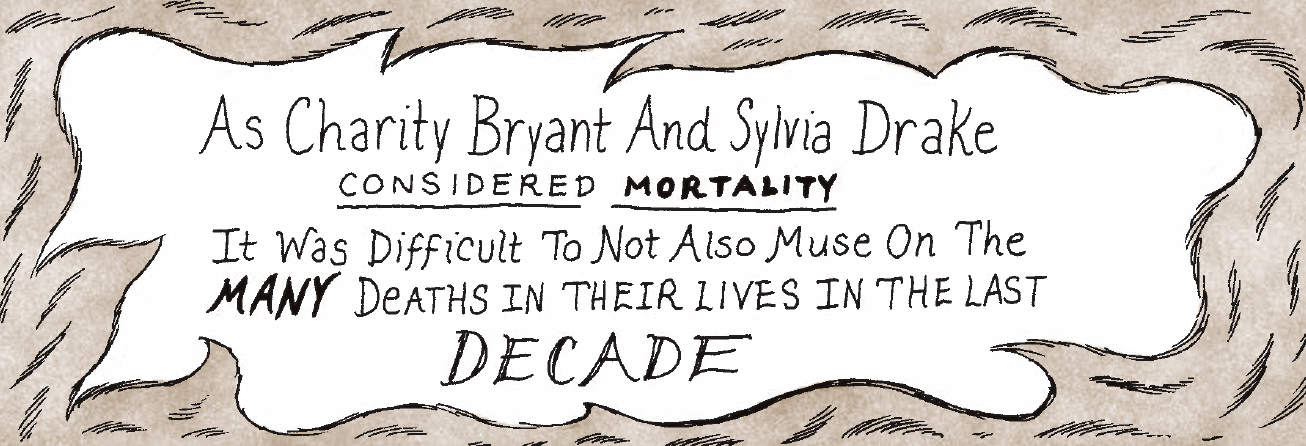

P. 161 - As Charity Bryant and Sylvia Drake Considered Mortality

All of these deaths are real, but details as to how each of them died are less clear. The only two who I know with certainty, thanks to Cleves, are Peter Bryant (tuberculosis) and Mary Manley (old age). But the timing is accurate - all of these people died between 1820 and 1830. It really is overwhelming when you think about how constant deaths presence was in Charity and Sylvia’s life. I’m nearly 30 and I can count on one hand the people close to me who have died. Sometimes I think this is one of the biggest gaps of experience between me and them. There is a lot I find myself relating to that they go through, but their understanding of mortality is so far away from what I know.

P. 162, P. 163 - Scold the Apprentices, Perhaps It Will Help

Cleves writes about the many apprentices they employed in chapter 15. I have greatly understated how many apprentices there were, and how close they were to Charity and Sylvia. Their apprentices lived with them for many years, and formed deep bonds with them. I was sad to not be able to include this more in the book, but space and timing made it difficult. There are already a lot of characters, and to add more felt like it would be overwhelming. Should you want to know more about their apprentices, look towards our Holy Mother of knowledge Rachel Hope Cleves.

Redgrave, 1845

P. 164 - The Limitations of Prayer

This is somewhat true. It is documented that Charity often missed meeting, and also that Polly and Sylvia maintained a close relationship all their lives. But, I don’t know if Polly actually attended this meetinghouse with Sylvia, and it’s likely she didn’t, because she lived in a neighboring town, not Weybridge. Would Polly have traveled a far distance to see her sister? Absolutely. Would Polly and Sylvia have likely discussed the loss of Achsah? Highly likely, as it was a significant event in both their lives. But, the setting itself is less convincing.

As a parent myself it is very hard for me to fathom the loss of your child. Working on this book affected me in a lot of ways, but I definitely found myself holding my son a little bit closer, and appreciating that he was born in an era where he is likely to live a long life.

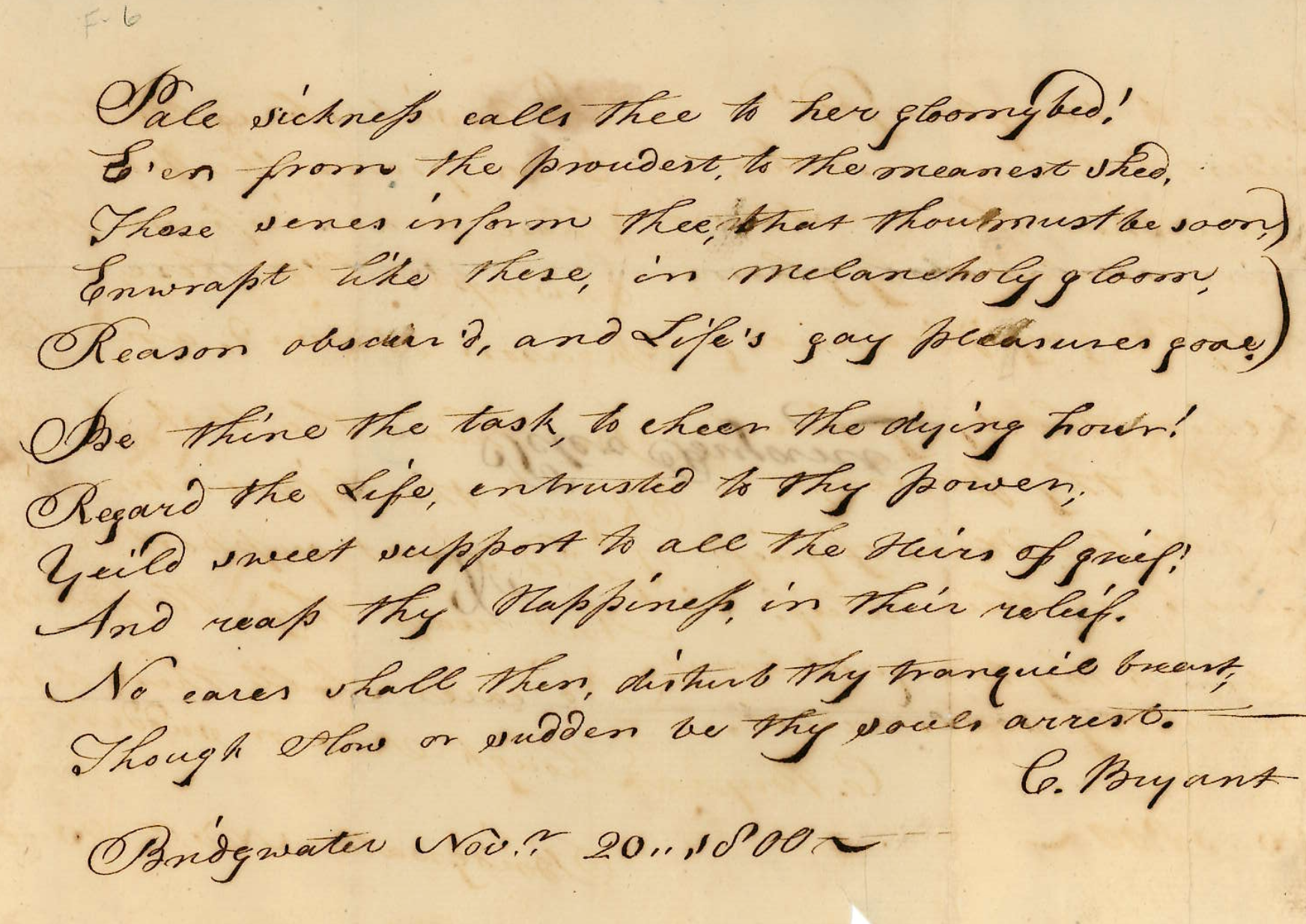

P. 165 - A Poem Written In Feeling

This is a real poem written by Charity in 1809. As you can see, I often use poems from earlier years later on in the story. This is because the majority of the writing I have from Charity is from earlier in her life. The full poem:

Sleep on, sweet girl, Oh! Nights my bosom prove,

Tho pillow and the cure of her I love.

That Oh! My bosom no relief can give;

No health restore, No drooping heart revive,

To There O heaven! Alone belong the power!

Thy Word can heal, Thy Mercy I implore!

To my fond sighs O lend a pitying Ear!

O send relief, this drooping blossom near.

O sink it not beneath Thy Chastening hand!

But speak the Word, it lives at Thy command!

O speak the word - and health with all her trim,

And smiling peace shall visit it again.

Despair and Gloom shall with thy Frown depart,

And joy and gratitude shall fill the hear.

Thy ways are night, I own thy sentence Just!

And O, forgive this particle of dust,

Who waved on Thee with humble hope depend,

And ask Thy pity for a suffering friend.

P. 166 - Middlebury Hustles, Middlebury Bustles

The details in this vignette are largely true. Edwin and Lucy Ann courted, and soon married. The Congregationalist Church of Weybridge suffered with mismanagement and a lot of Minister turn over. My evidence for mismanagement comes from letters written by Eli Moody where he writes of not being paid what he was due as head of the Church, and he spent many years complaining about it to Charity, and begging her to chase them down to pay him. There was also a lot of turnover in ministers for reasons opaque to me.

Eli Moody really did leave because of ill health, and he speaks of it in his letters at the Henry Sheldon Museum. In an 1824 letter he says:

“The providence of God, which separated me from you, still looks to me dark + mysterious. Why was it to be so? This enquiry often arises in my mind, while reflecting on the painful subject. To furnish an answer to it, I am not able, unless I say ‘Even so Father, for so it seemed good in thy sights.’ That it was my duty to leave you, I think the change in the state of my health since I came away, affords additional evidence. What is before me in the dispensations of Providence, I know not, but in view of what is past, I have but become more and more confirmed in the belief, that the course which I took was clearly pointed out in the indications of Providence. And I hope the change will be overruled for the furtherance of the Gospel, and the salvation of Souls among you.”

And of course, the history of railroads in Vermont. Spoken of for a while before they were actually built.

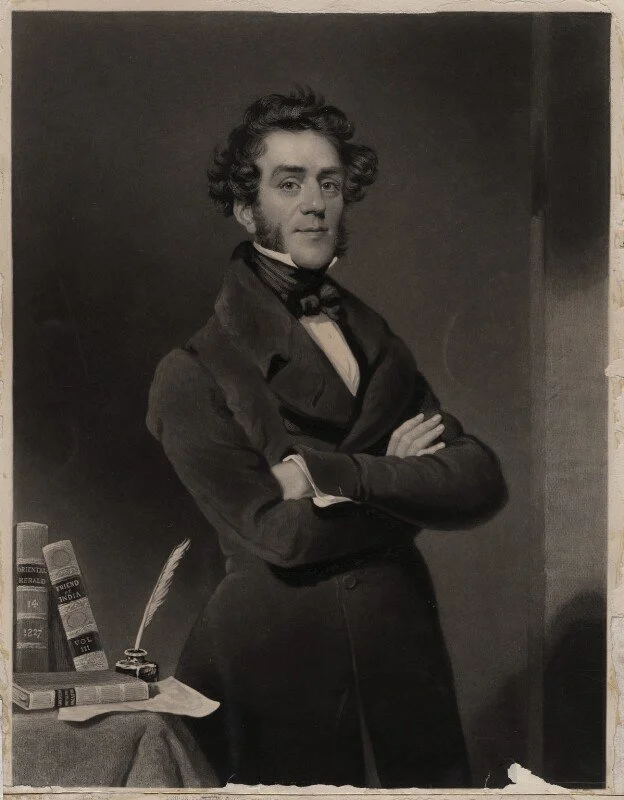

P. 167 - Reading of the Account of Mr Thompson; British Abolitionist

This is true. Sylvia mentions reading this account in her journal (though she misspelled Thompson):

‘C, B D come before 10. Read, give pleasing account of Mr Thomson the English agent for the abolition of slavery.’

I have searched for evidence amongst all the papers at the HSM of what Charity and Sylvia thought of slavery. There is very little. But, this small mention sheds some light. By referring to the account as ‘pleasing,’ I took it to mean that Sylvia, at the very least, did not find the material offensive.

I am fairly certain that this is the text that Charity and Sylvia read, and it is what I am quoting from.

George Donisthorpe Thompson

P. 168 - A Letter from Eli Moody, A Missed Presence

This is an abbreviated version of a real letter from Eli Moody to Charity Bryant in 1824 at the HSM. It is quite long, but for those intrepid and interested enough to read the full text, here it is:

Very Dear Friends,

Your interesting letter mail’d April 26th has come safely to hand. It was to us indeed a welcome messenger. We are anxious to hear from you after, lest your situation in the providence of God, be what it will. But when we can learn that Miss Bryants health has considerably improved, and that Miss Drakes is as comfortable as it has been, it affords us much pleasure. Soon I trust we can safely say that our friendship for you, prepares us, at all times, to take part in your joys and your sorrows. We are therefore prepared while we rejoice with you, in view of all the movies you receive, to sympathize with you also under all your trials. While you speak of your prospects as a Church and People, you speak of Darkness, which now hangs over you. To be sure there are circumstances which render your prospects dark indeed, if your dependence was wholly upon an arm of flesh. But I hope you do not consider your grat strength as flying in such weakness, but that on the contrary, your hope will be ‘in the living God’ and your help be looked for from him. Good thing Asa when praying unto the Lord, at a time in which he and his people, greatly needed special Divine interposition, could say ‘Lord, it is nothing with thee, to help, whether with many or with them that have no power, help us, Oh Lord, our God, for we rest on thee, and in thy name we go against this multitude.’ This prayer you know was heard and answered in mercy. The lord, my dear friends, is the same now that he was then. And is as ready to help those that in themselves ‘have no power’ if they but ‘rest on Him’ and go forward ‘in his name.’

If your trust is in God and your desires continue to ascend to him, you may believe that from some quarter the lord will ere long send you help. The blessing for which you hope and pray may come from a quarter to which you are not looking, and in a way which you have not expected. If you trust in the Lord, he will help, but will do it in such a way as to ‘stain the pride of all human glory,’ and to exalt his own grat name. I hope that before this time, the darknend cloud, has in some measure at least been withdrawn. And that you can speak of the mercies of the Lord, with truly grateful hearts. He can clear the darkest skies, and give us day for night.

The death of our beloved sister, Mrs Ripley, I had heard of, before your letter arrived. May this afflictive Providence be sanctified to the family, and to the church, which by it has been beareved one of its valuable members! It is a solemn consideration, that one Praying Soul, has been removed from among you. The call is loud, on the living, to be more earnest in their suppliocations. So our generation is fast hastening from the world, one after another, and our turn, as individuals, must come soon. May the gracious Lord, who has the hearts of all men in his hand, and with whom is the residue of the Spirit, grant his Divine influences to bring many among you to repentance, and thus prepare them to come and unite themselves to his Church, so as more than to fill the vacancies whihc are made in the midst of you, by deaths and removals! I cannot but hope that the next letter I recieve from you will bring some good tidings, of good things bestowed upon the beloved Church and people of Weybridge.

Miss Drake speaks of a destitution of feeling on the subject of religion, and of being absorbed in the cares and concerns of the world. These things, we all know, we ought not to have occasion to speak of. And I hope, my dear sisters, that you, neither of you, now have occasion to speak of them. May I not hope that you are both soaring on the wings of faith and love, and are fast pressing forward in the way of the heavenly —! May I not hope that you let your lights shine, so that all who behold you are constrained to bear witness that you have been with Jesus! We have but a little time to spend on earth. What we do, here, for our Lord and Master, must ‘be done quickly.’ Let us then ‘not be weary, in welldoing’ on slothful in the service of him who has died for us. We shall not, my dear friends, lament in the eternal world, that we did so much for God in this. And happy will it be for us, if we not so live, that we shall not then have occasion to lament, that we did so little. If we indeed love and serve the Lord, the Crown of glory which we shall receive, when we shall ‘have accomplished — circling our days,’ will more than ten thousand fold reward all our labors and our toils and our sufferings. Let us then with unwearied diligence, do the will of our God, while he is pleased to continue us on his footstool.

You say the few females who assemble for prayer, you think from what you can learn, appear to feel more than ever the importance of that duty. This, I am much rejoiced to hear, as I consider it an omen for good. I hope you will be able to tell me in your next, that all the Church, feel more than ever the importance of prayer, and are earnestly imploring the blessing of heaven. If you could tell me this, if you were not able at the same time to tell me that sinners among you were flocking to Christ, I should feel the assurance, that soon, I should hear this joyful news. And I should also expect that the time was not far distant, when a Minister would be given you in mercy. You say you wish to know what answer to give to people who enquire whether we shall not visit Weybridge next Autumn or another, you say, you wish me to furnish you with such an answer to this question, as will be most gratifying to your feelings. I wish my dear friends that I could, because to gratify your feelings, certainly would afford me much pleasure. And to assist you, and others whom I esteem my friends, who were of my beloved People, (were it practicable) would afford me more pleasure than a visit to any other absent friends on earth. But think it not probable, that it will appear to be my duty. My health continues — comfortable. With the exception of a very few days, it has been as — since, than when, I wrote you last. I can now perform the ordinary vices of the Sabbath without any considerable fatigue. I have had an application to supply, at South Hadley Council, (where I was preaching when we wrote you last) until next NOveember, and have thought it best for me to engage to do it, on corelition that my health should be as good that it would not be expedient for me to journey on that account. I have reserved to myself the right of leaving the people when I please to journey to the Salt water, or to spend the warm part of the season on the Sea Board, if the state of my health should be such as to require it. I have thought that if the state of my health should require a journey, I had better go to the Saltwater, than to the north. But I am at present encouraged to hope that I shall not, on that account be under the necessity of journeying either way. And if my health should become — I have thought, as I can have steady emplyment this summer, I had better continue to labor, and omit journeying on visits, for some future opportunity if life should be —. For these reasons I now think it not probable, that we can visit Weybridge next Autumn. Could we do it, it would afford us much pleasure to have your good company down. I conclude you, and Laura, will not fail to visit us, while on your tour next fall. We shall continue to make our home in this place, for the present. If we go from here in the course of the summer, we will let you knowof it, and where we are. Mrs Moodys health, I think, is as good as it has been for considerable time, and I hope is improving. There are now no revivals of religion in this vicinity, but a general stupidity and coldness prevails. The congregation to which I preach on the sabbath is small but very attentive. I hope that my labors will not be wholly in vain among them. We shall hope to hear from you again very soon. Mrs Moody unites in love to you both. Please to remember us affectionately, to all our dear friends whom you see. Thank you for notcing your letter from Jane, and wish you to give our love to her, when you write her. Wishing an interest in your prayers. I am as ever, your friend and brother, E. Moody

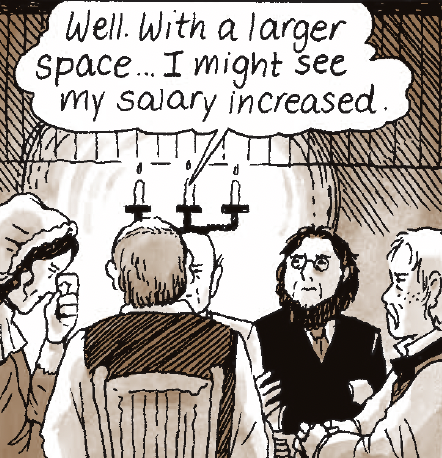

P. 169 - A Meeting of the Leadership

This is somewhat fabricated. Charity was very involved in the church, that’s true, and a new church was built some years after this. Asaph Drake was a Deacon, and very involved as well. But, the conversation is largely imagined.

P. 170 - Sleep, Tender Sleep, Cannot Be Found

This sequence was inspired by a few passages in Sylvia’s journal:

“Awake before the dawn of day + reflect on the stupid, wicked life I live.”

‘“wake before the dawning of the day, no very fit reflections.”

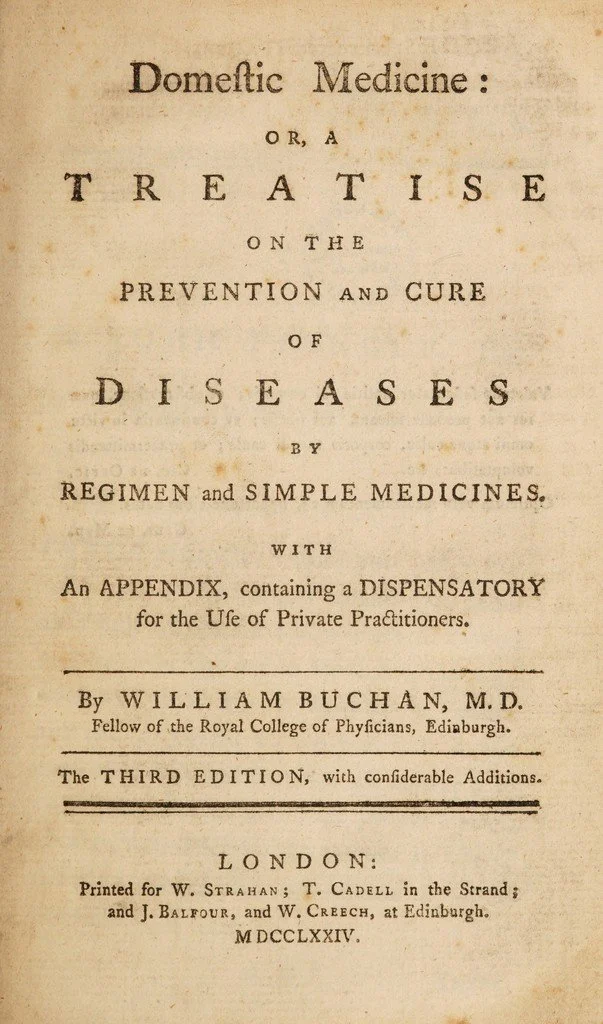

P. 171 - The Many Attempts and Medicines

This page is entirely based upon research in Cleves’ book. I am eternally grateful to her for writing at length about the ways these women tried to heal themselves.

I was also inspired by the book with the very short title: Domestic Medicine: Or, A Treatise on the Prevention and Cure of Diseases by Regimen and Simple Medicines.

P. 172 - A Letter Penned To Charity’s Brother Peter’s Widow: Sally Snell

This is a real letter from Charity to her brother Peter’s wife, Sally Snell Bryant. The letter is a part of the archive in Illinois at the Bureau County Historical Society. Sally and her children relocated to Illinois, leaving Massachusetts, which is why some of Charity’s only letters that remain are in Illinois, not Vermont. Part of the 1833 letter is pictured below.

Pyne, 1827

P. 173 - The Question of Mathematicks

Sylvia notes in her journal at the HSM: ‘Johnson says a woman can’t know too much arithmitick.’ which inspired the passage. It was not actually said by Asaph, but Asaph ended up playing the role of my curmudgeon, so I applied it to him. Emma Willard, as mentioned previously, was a real woman and educator. As to their business, and their success, Cleves notes that Charity and Sylvia actually managed economically better than a lot of their family members because tailoring work remained consistent.

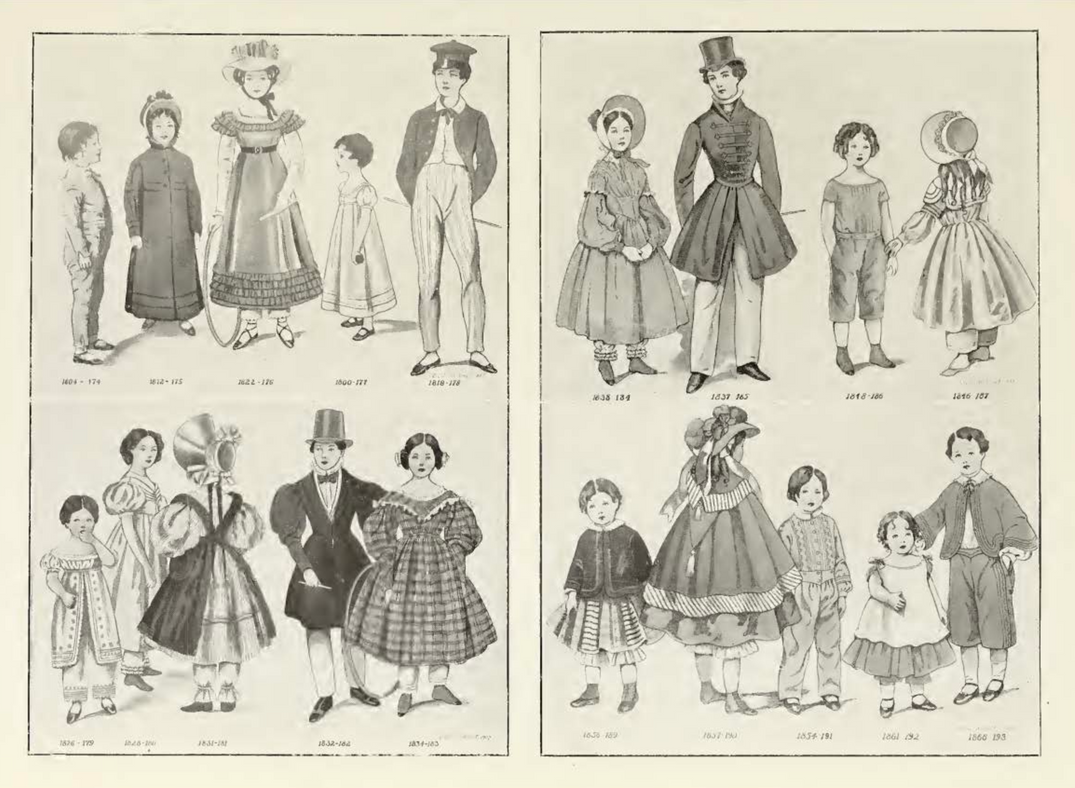

Prior, 1843

American Duchess, 1820

Philadelphia Museum of Art

P. 174 - Ephesians 2, And A Journal Entry Penned By Miss Drake

This is a real biblical passage, and the writing is all actually from Sylvia’s journal. But, the writing is spread out around her journal, and I combined phrases to form a single passage. The most illuminating of her phrases came from this section of her journal:

“Life with a lamp without oil. Giving way to temptation which leads directly to sin. The solemn midnight hour harrows up my recollection, recalls to mind my awful misgivings. Unbind the bolted door to my depraved heart + spread despair and horror o’er that countenance which has so lately been cheered by folly + vice.”

In the first rough outlines of this book I imagined each section of the story would be titled, and I liked the idea of calling a section ‘Life with a lamp without oil.’ This did not come to fruition in later drafts, but what holds true is that I really do find Sylvia’s writing vivid. Charity was the one who often was complimented for her writing, but I am often impressed by Sylvia’s way of describing her life, and saddened by the intensity of her self-hatred.

P. 175 - Tarrying at Asaph’s Home, Mending To Be Done

Sylvia often went to relatives home to complete tailoring work. As she writes in her journal “We go to Br Asaphs to work.”

She and Charity also continued to take trips to Massachusetts, more than I mention in this book.

Sylvia also writers of unresolved feelings about her Mother’s death in her journal:

“6 years ago today my Dear Mother spent her last sabbath on earth.’

‘How often has a recollection of her sufferings sprang in upon my mind as I open’d the apartments which I then so much frequented. The falling snow, the dismal storm, the nightly scene all remind me of the sufferer. Oh why dwell so much! ! !”

P. 176 - Let the Tears Fall

This is a real poem written by Charity in 1800. It is archived at the Bureau County Historical Society, and pictured below.

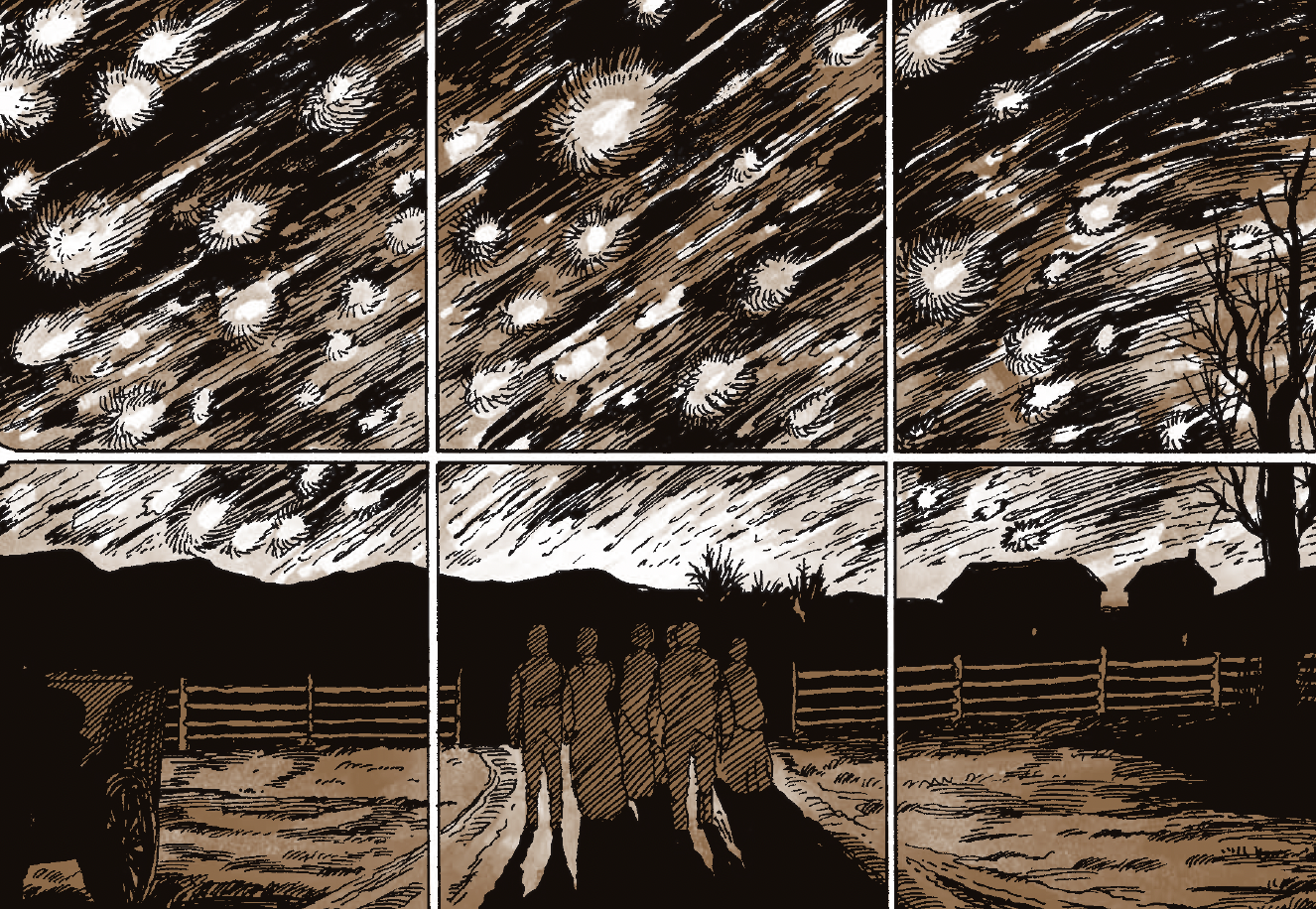

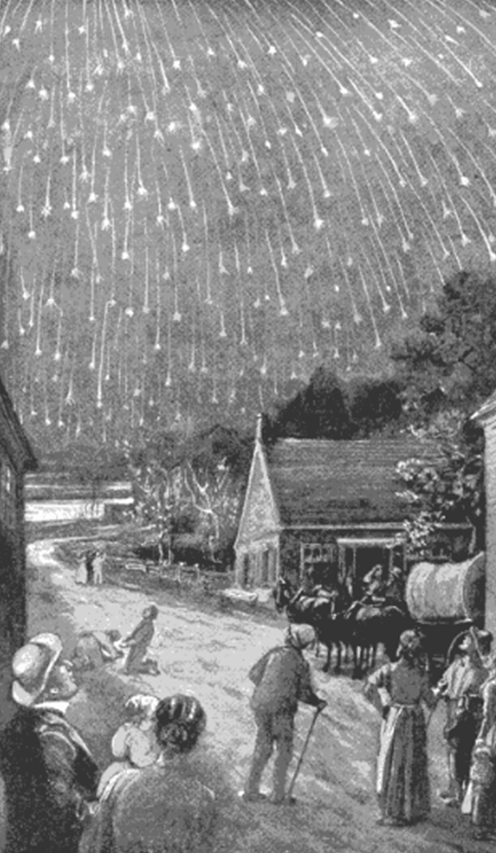

P. 177, P. 178 - A Good Show

The conversation is imagined, but the event is real. There was an exceptional meteor storm in 1833, visible in the town of Weybridge.

P. 179 - A Brother and Sister in a Cemetery

This is mostly true. Mary Manley was buried in the Weybridge cemetery, which was situated between Asaph and Sylvia’s home. It seems likely they would go at some point. And Sylvia did ultimately live with Asaph after Charity’s death. When, and if, they discussed it beforehand is unknown.

There is mention of a stove being dropped on someone’s foot briefly in Sylvia’s diary, and I felt compelled to work that detail in somewhere.

P. 180 - Asaph is Correct, Mud is Worse

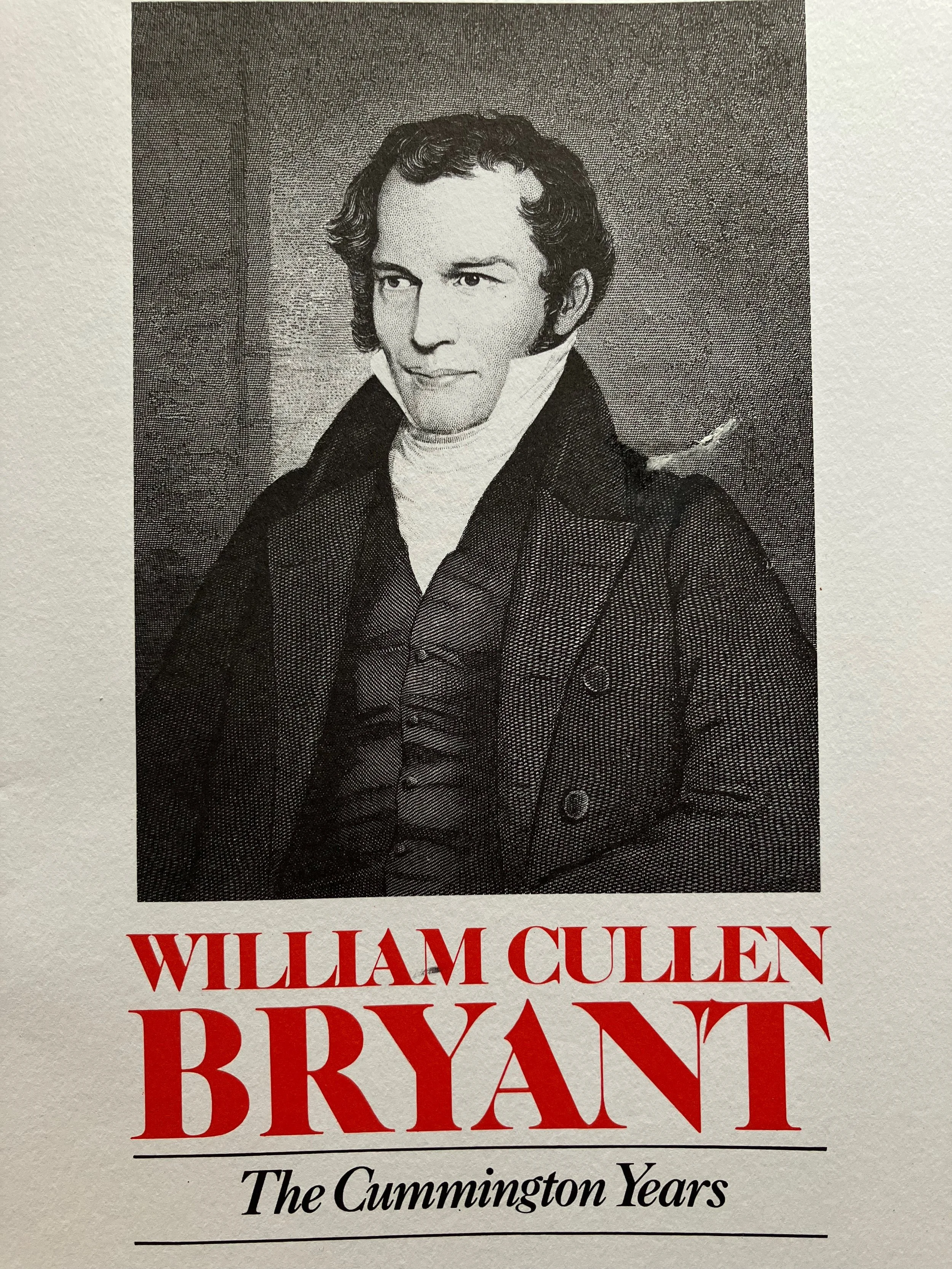

This is all true. They made the long journey to Massachusetts, and the mentions of family are all real. William Cullen Bryant was a renowned enough poet with published work. For Silence, she has many letters saved at the HSM. And her life was, indeed, very hard. Lydia Richards was also still very much in contact with Charity at this point in life, and there are mentions of visits with her in person in Sylvia’s journal at the HSM. She writes at one point “Lydia has her son Noble with her.”

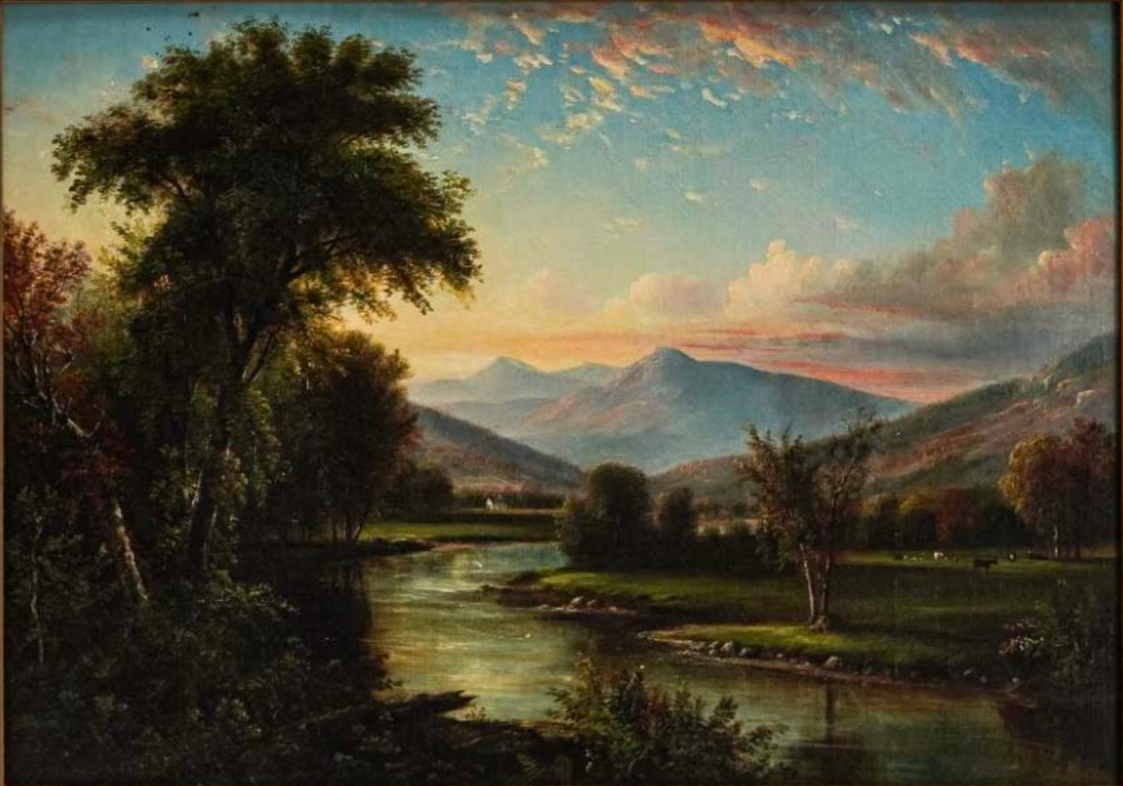

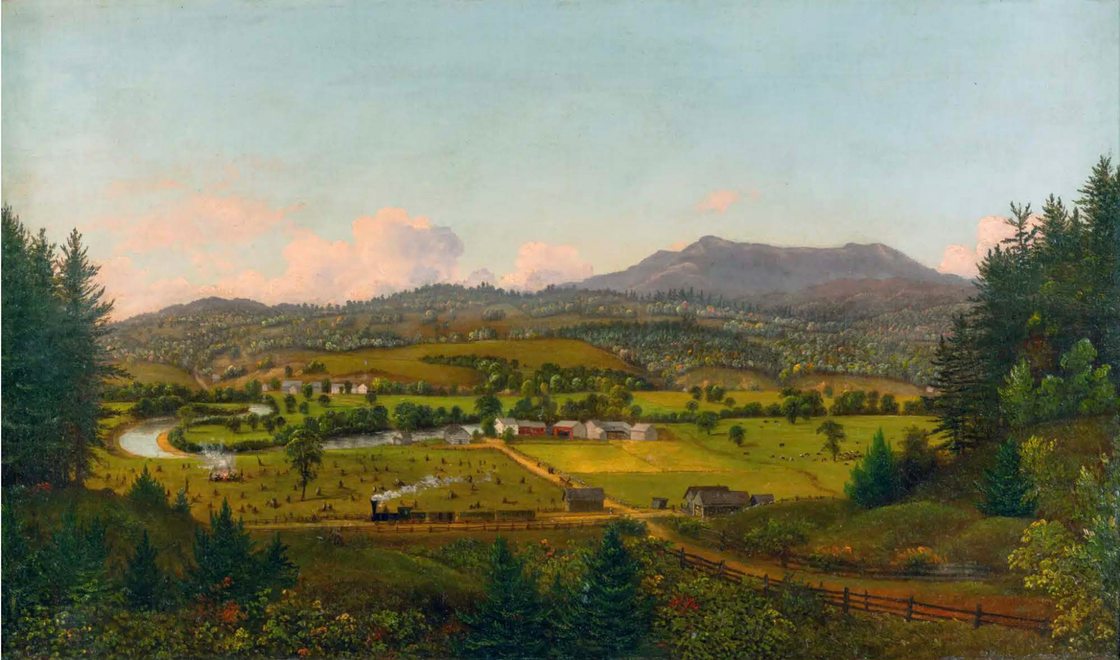

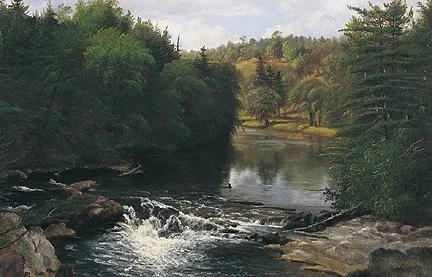

Paintings - Heyde

P. 181 - The Scents and Sensations

This is fabricated. I am imagining, to the best of my ability.

P. 182 - They Will Indeed Be Late

This is fabricated. The following pages about their viewing of the petroglyphs has no evidence to it. I worked it in to call attention to an important, and very real, example of Indigenous presence in Vermont.

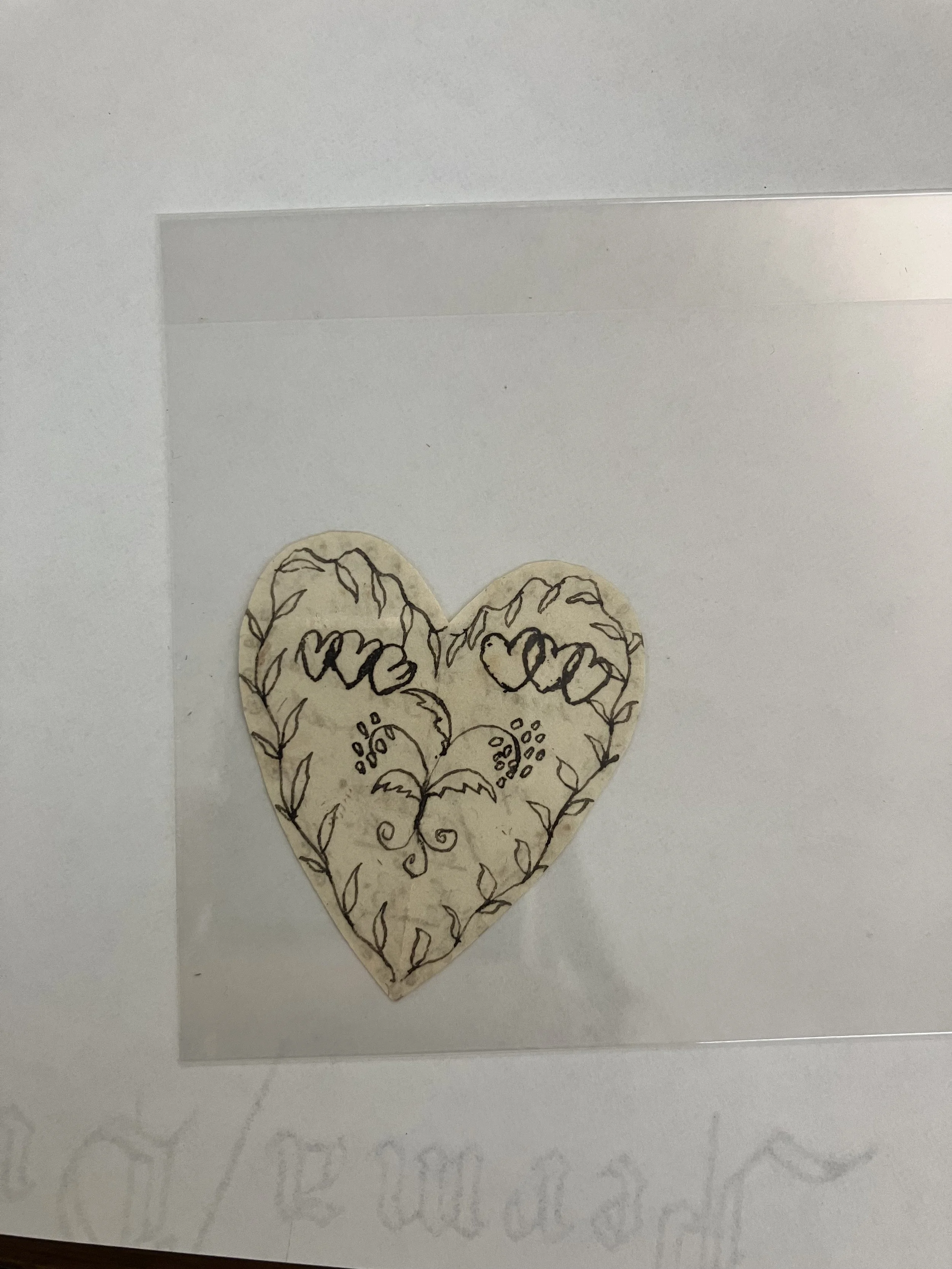

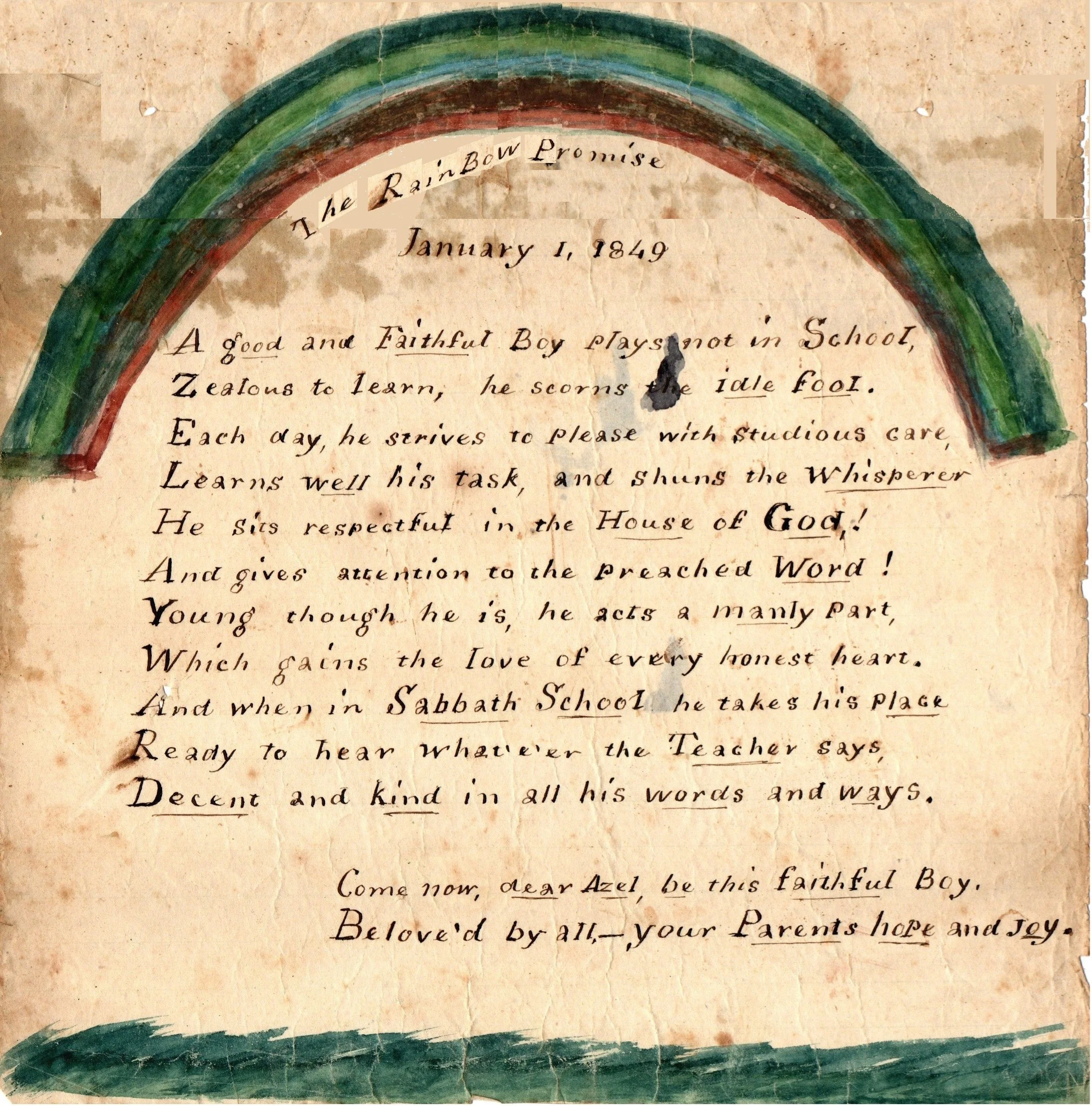

Sylvia notes she is ‘no good at picture drawing,’ which is a slight nod to the fact that Charity seems to have doodled occasionally. I have only two examples of her art - a rainbow, and a heart.

P. 183 - They Are Petroglyphs Made By The Sokoki Abenaki 3,000 Years Ago

Read more about them! Sylvia’s mention of Charity’s interest in Indigenous people’s comes from mentions in her journal of what Charity read:

“Mr Belding visits us, reads the story of the Indian Cottage”

“Miss Wood has to hurry to get ready for school. Ms B read in the Redeem’d Captive Turning to Zion”

P. 184 - We Are The Elderly In The Room (We Did Not Used To Be)

Somewhat fabricated. America changed greatly in there lifetime, and I don’t think it’s stretching to say that they noticed it. Charity was born in 1777, just one year after the founding of the United States. But, I have no actual evidence of conversations they had while on their trip.

The song referenced is a real one, and Sylvia often mentions singing at dinner’s in her journal. She also mentions going to singing school back in Weybridge, a lovely detail that I failed to fit in the narrative.

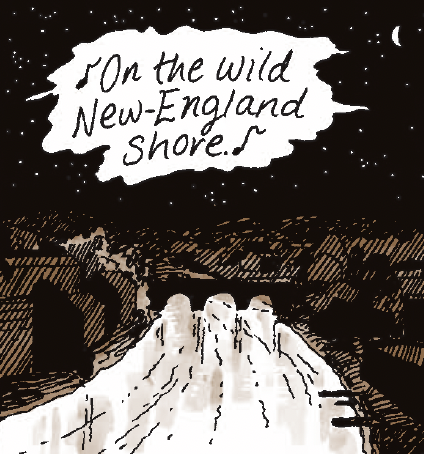

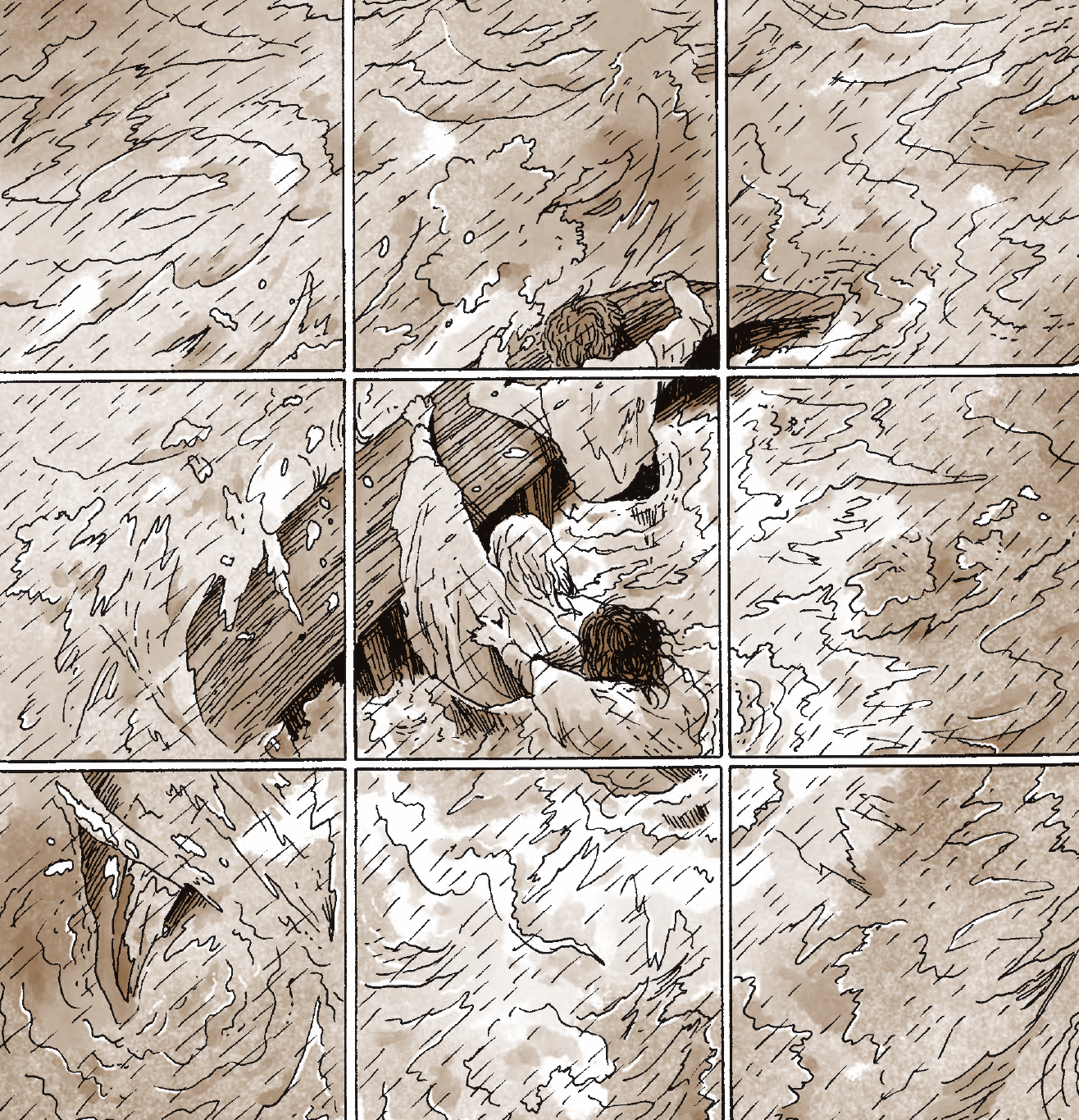

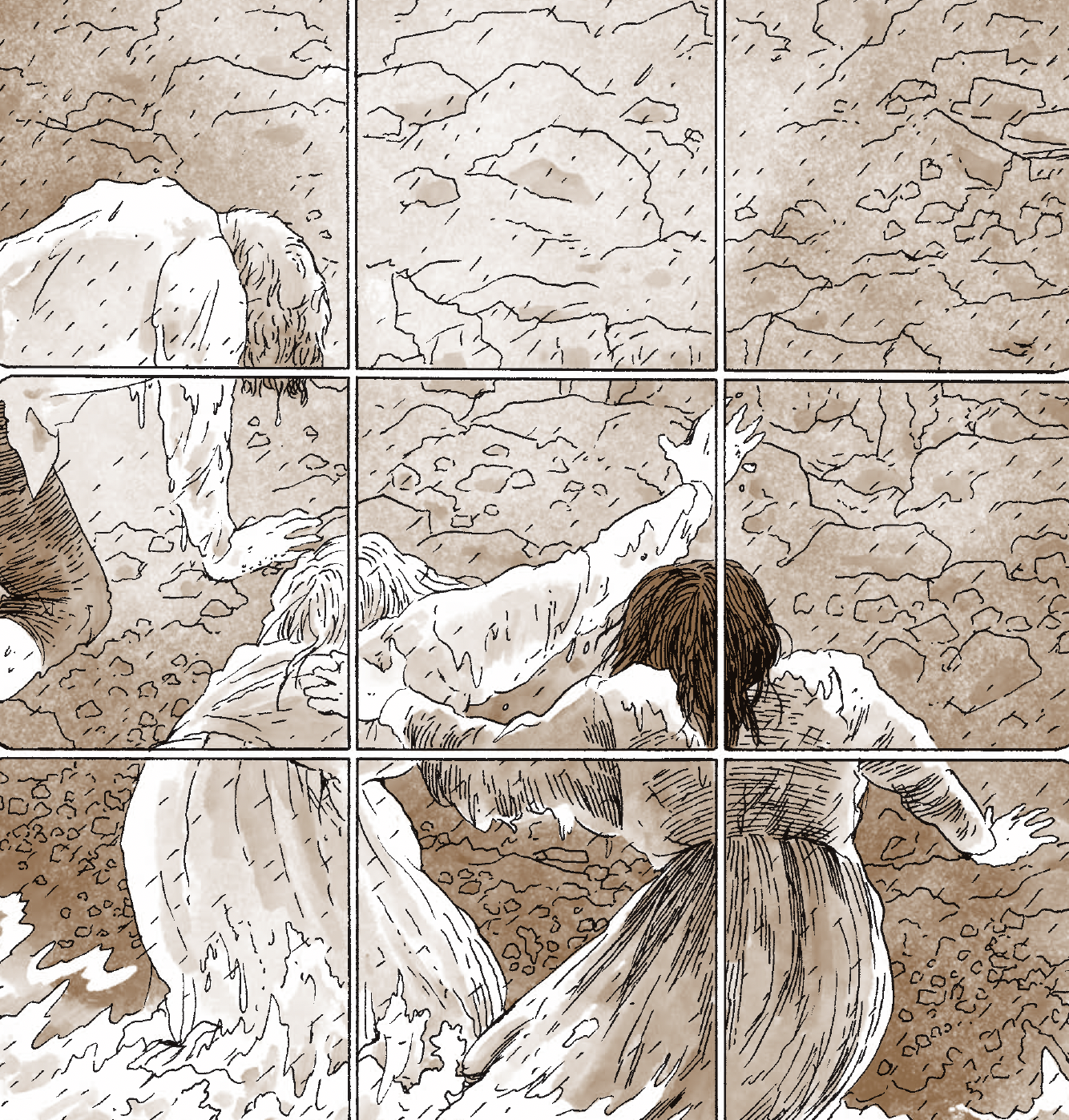

P. 185 - 189 - They Will Very Nearly Die, They Will, Very Nearly, Die

This entire sequence was based upon an entry in Sylvia’s journal about an experience on a trip to Massachusetts:

“Have just experienced much of the goodness of God in being assisted over deep and dangerous water by a young stranger. Our trembling limbs could scarcely support us, or our tongues utter the thanks due. But the grateful emotion of the soul was very visible on our cheeks.”

I knew as soon as I read this that this would play an important role in the story. So much of Sylvia’s diary, which was arguably my main source of information, is about the mundane. And any mention of an extreme event caught my attention.

I was really dreading drawing these pages initially because water is, you know, hard to draw. And I’ve also never really gotten the hang of boats. But when it came time to draw it I found it flowed out of me easily. Sometimes the imagined page in your mind is much more daunting than the real one.

P. 190, 191 - The Words Are Bitter, They Will Both Feel Regret

This sequence is inspired by true passages, though the conversation is imagined. First, logistically, right around the passage mentioned above, Sylvia describes more details of their trip:

“Ride, rain, conclude. Thunder all night.

Make friends on the road, ride with them to Walpole. Pass over one bridge, almost wash’d away. 3 kind strangers get our horse and waggon threw.

Rest up at Natts at Pitts ford Corner. We take leave of our accommodations, pay 34 cents, call at Brooks in Clarendon, walk up 2 hills, call at Finney, Pay 10 dime, pay 17 at toll gate.

Pay 42 cents, ride as far as the greens. Heavy shower. From there to private home + dine. They shown much kindness. Build a large fire to dry us, set the table. Gate fees 34 cents.”

But, most significantly, the heart of this vignette comes from a single line Sylvia wrote in her journal: “C mentions that we should be unwilling to have even our fellow creatures know our thoughts.”

I cannot describe my elation when I read this line. For once, in hundreds of pages, Sylvia gave me something vulnerable. Of course, Sylvia says nothing more about it after and moves on to notions of religion and chores. She doesn’t mention a fight, or it leading to any kind of impasse in their relationship, but the text itself is illuminating enough. It shows the Charity did hide herself, even from Sylvia. And for Sylvia to dare to mention it, even briefly, is also interesting. I can’t tell if it shows agreement or disagreement. Regardless, this is what influenced the creation of this vignette.

P. 192 - For Who Would We Be Without One Another?

The facts themselves sometimes tell the whole story. Charity and Sylvia lived together for 44 years. Only death parted them. Their commitment to one another was clear, and enduring.

More outfit inspiration from Dickinson

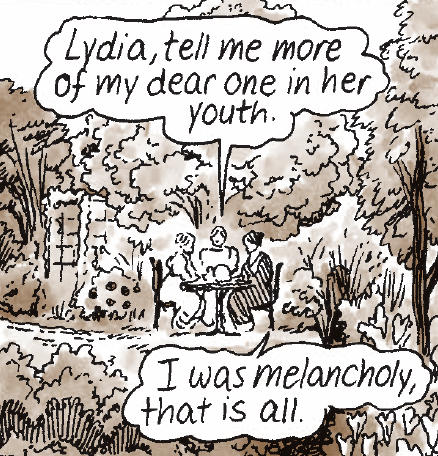

P. 193 - The Charming Lydia Richards

There is evidence that Charity and Sylvia spent time with Lydia in Massachusetts, but no details remain of the content of their interactions. What there is evidence of is that when Charity was a young woman she had a romantic encounter with Lydia in a garden (chapter 9, Charity and Lydia), as detailed in Cleves’ book. I chose to echo that reality in this meeting, many years later.

Charity also did indeed have many encounters with women in her youth. Cleves describes them in much more detail than I get to.

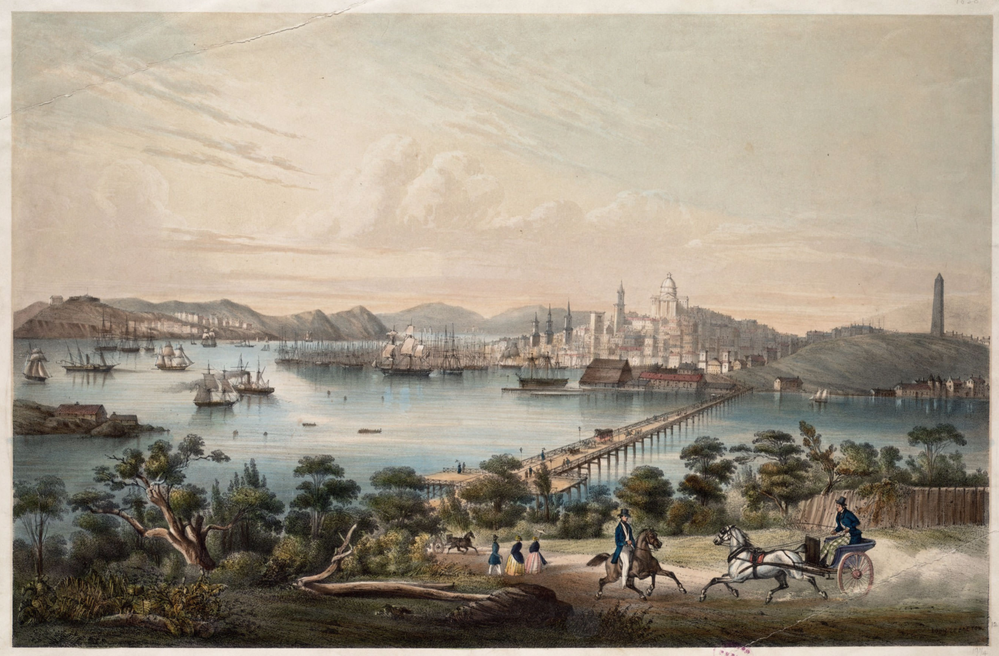

P. 194 - Boston, Glorious Boston

Pretty straightforward. Boston was bustling, it’s recorded that they visited. As someone who lives in a small town in Vermont I often feel overjoyed at going to a city, but then quickly realize I am happy to live where I am. So the dialogue is actually about me, but I like to think Charity and Sylvia felt similarly.

Winslow Homer, 1857

Boston 1830s

Le Breton, 1840

Cecil Trout 1830s

P. 195, P. 196 - The Happiest of Visits

Charity and Sylvia saw William (whose nickname in the family was actually Cullen) throughout their life, but I have no evidence that they actually saw him at Silence’s house. I decided to put this scene here because it meant I could expand on two characters at once - Silence Bryant and William Cullen Bryant. The name of his wife is true, and they had multiple children together. William was indeed political and wrote about abolition and economics. And of course, Vermont really did vote in favor of John Quincy over Jackson in the 1828 election.

At the very last minute while drawing the last 60 pages of this book I came across a booklet with an engraving of WCB as a young man. I was eternally grateful and was thus able to draw him accurately. Until that point I had only ever come across portraits of him as a very old man, and it was hard to picture him younger with a giant beard…

P. 197 - It Did Not Matter That the Fire Had Gone Out

I opted to show Charity and Sylvia’s intimacy discreetly to reflect the understanding of sex at this time. Charity and Sylvia were modest, Christian women, and while I don’t want to undermine the reality and beauty of two women loving one another, I did want to express it in a way that fit their lives. Sometimes I imagine them both lifting out of their graves and flipping through this book. My guess is their first horrified reaction would be that I depicted them kissing, and then some.

P. 198 - Rise, It Shall Always Be Difficult

All of these deaths are real, and the graves are drawn to reflect the actual ones. I was not able to visit the cemetery in Massachusetts in person, but photos online showed me what I needed.

P. 199 - A Portrait of the Bryant Family

Fabricated, of course. But hopeful nonetheless. This is the kind of page that, in my mind, could only work in comics. You can inch into new realities so quietly and seamlessly in a comic.

P. 200 - Vermont Has Missed Them

On their journey home I chose to depict in the background the route through the mountains that I myself had to drive to reach the Henry Sheldon Museum in Middlebury, Vermont, from my home in the Upper Valley.

P. 201 - Poor Mrs. Elmer, Poor Child

Nearly all true, and taken from Sylvia’s diary:

“Arrive home after sunset, hear of death of Sally Slickneys little son scalded in hot cider. Lived a week after the accident had taken place.”

“Mrs Elmer + Goreham get badly bruised by falling out of the waggon, the horse breaks his leg… we go to sisters to render assistance. We make the poor horse two visits.”

Edwin and Lucy Ann did marry, though he marriage of the Hagar boy mentioned is fabricated.

Barn reference from, you guessed it, the Shelburne Museum.

A Letter from Mrs. Lydia Richards

This is real, but from an earlier time than in the story. The text can be found in an 1826 from Lydia to Charity at the HSM. An excerpt:

… I feel, my dear friend, that the opportunity which I had with you, when here, was not equal to what I could have wished, and some things were left unsaid, which I could wish had been said. O how unsatisfying in all earthly good! How desirable to — thou durable riches, that heavenly treasure, compound with which flies before the wind, or smoke, which vanishes in air!

The children have retired. Mary wish to know if I was going to write to ‘Aunt Charity.’ said I must give her love to you, and she added, ‘to Miss Drake too.

P. 203 - To Build is to Realize

Real. The congregational community built a new, and bigger church in 1847, as mentioned in this history.

P. 204 - There Were Two Bedrooms Unoccupied

I do not actually know how many bedrooms were free in their house, but I do know that this event actually happened. Sylvia notes it in her journal, briefly: “A black boy call + wish’d to obtain lodging but refus’d.”

I found this very compelling, and an important example of how surface level beliefs can be. They read of abolition, Sylvia referred to the accounts as ‘pleasing.’ But when a person of color came to their door looking for a place to stay, they were turned away. And based on all descriptions of their home I find it hard to believe they lacked space.

P. 205, P. 206 - The Horse Shall be Named Abigail

As mentioned earlier, Sylvia wrote of Ms Elmer’s horse dying, and of visiting it with Charity. After reading that passage I chose to imagine it a little differently, and have Charity go on her own. The name Abigail was chosen because of mentions in Sylvia’s journal of their reading accounts of the life of Abigail Adams.

I’m not quite sure how this all came together, but for some reason while working on the draft these disparate journal entries became linked in my mind - the boy being scalded to death, the horse getting injured, and their nephew getting married. Sometimes when you’re writing everything comes together exactly as it’s supposed to, and this was one of those moments. When I was writing out the word ‘matrimony’ and saw the panels on the page slip out of existence, I actually felt a chill. It reminded me of how I thought about marriage as a kid. I knew I was gay, and I knew it wasn’t legal for me to marry. When I would daydream in school and try and picture my own wedding, it was blank. My mind wouldn’t even let me imagine, as if the law had extended into me. I don’t remember feeling sad about it, it felt just like the way things were. When I was 19 years old the right to marry became the law. And while I was grateful, elated, righteous, I will always have lived my entire childhood without it.

The day I got married - June 20, 2021 - was a beautiful day. It was sunny in Vermont. My wife and I were married by our Rabbi in a ceremony with no people. We didn’t want anyone there, we just wanted each other.