BIBLIOGRAPHY

PART ONE

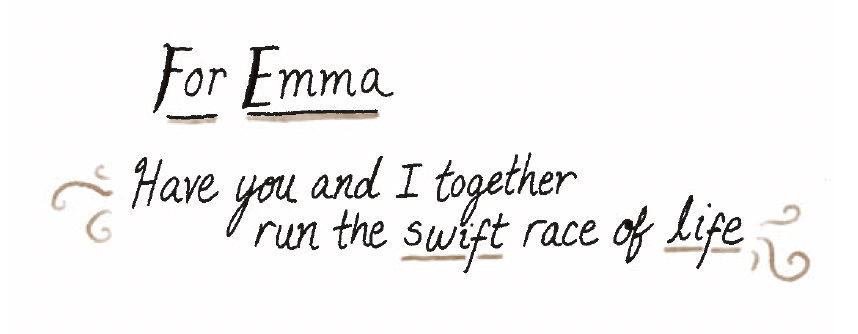

P. 5 - Dedication

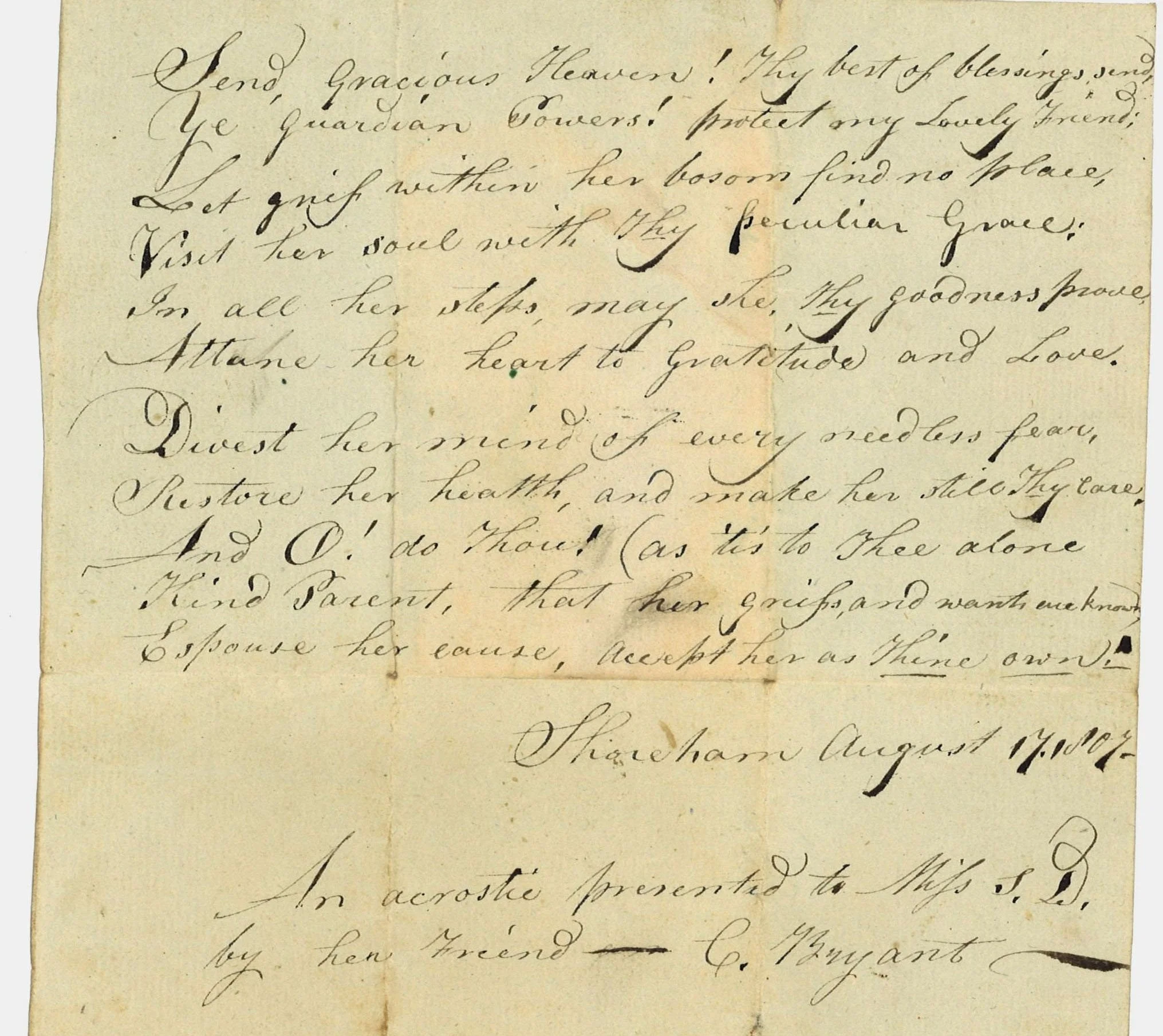

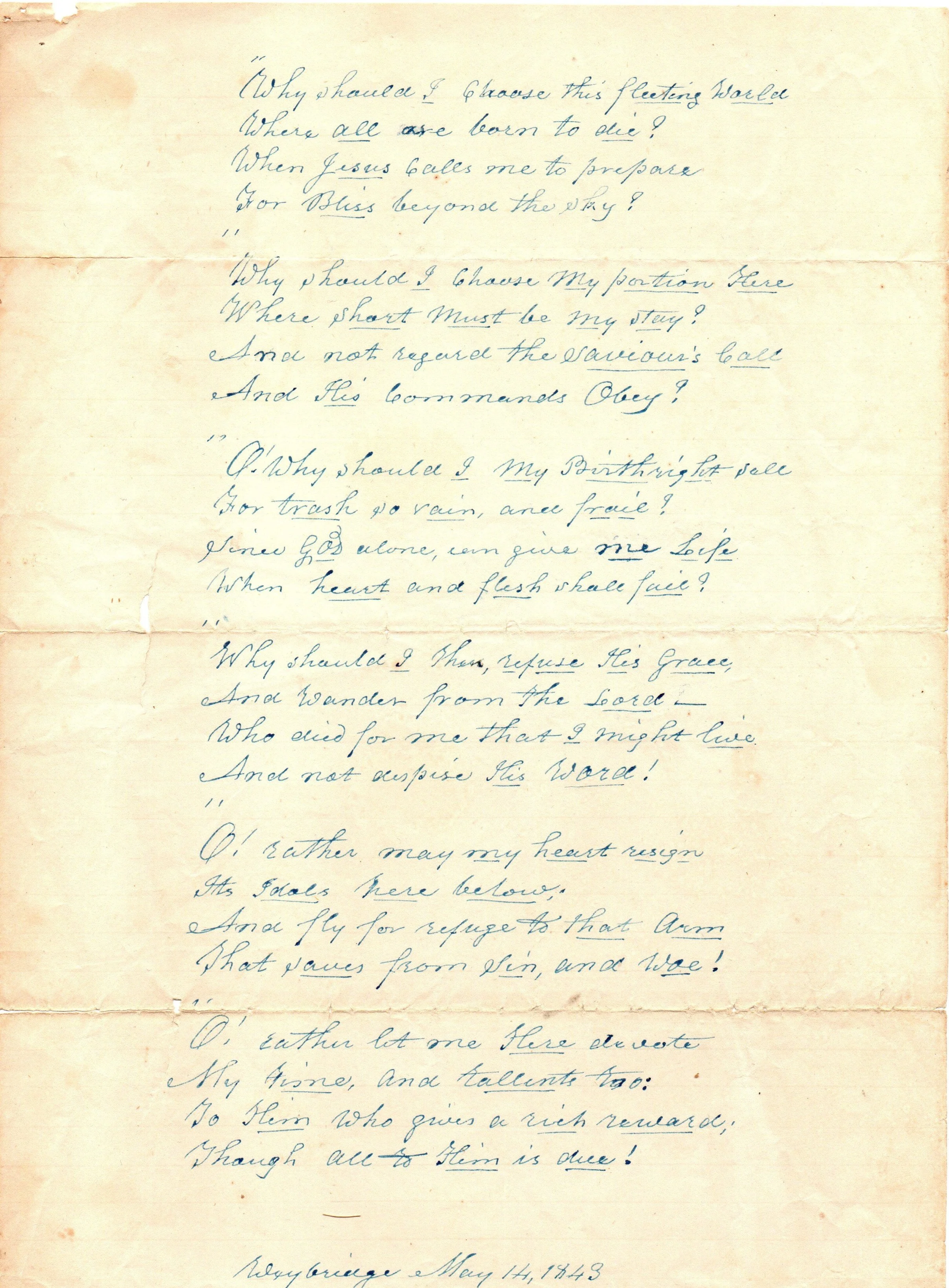

This text comes from one of Charity’s poems that is at the Henry Sheldon Museum in Middlebury, Vermont. You will see the Henry Sheldon mentioned many times in this bibliography - it is where the majority of their papers remain.

This poem was written in October 1847. Here is the complete stanza it comes from:

And more than forty years

Have you and I together,

Run the swift race race of life

In fair and stormy weather.

The above mentioned Emma with our tiny new son

P. 7 - The Day Wears On (and On)

There is no exact record of how Charity and Sylvia first met one another. All that is certain is the basic time and place. Charity did indeed take a ride in February 1807 with Dr. Shaw to get to Polly Hayward’s house (Sylvia’s sister), as noted in Rachel Hope Cleves’ book Charity and Sylvia, chapter 10. And they struck up a friendship quickly, with romance soon to follow.

Polly’s family however did not live in Weybridge. They likely lived in Bristol, according to the archivist Eva Garcelon Hart at the HSM. But, I moved them to Weybridge for this story in order to keep the locations consistent.

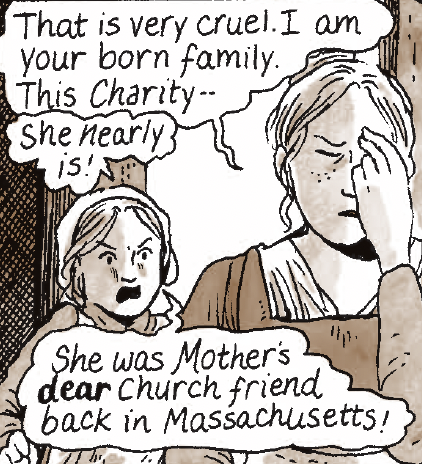

Achsah is indeed the eldest daughter of Polly and Asaph Hayward, but at this point in 1807 she would actually be slightly older than I draw her - she was 13 in 1807. Achsah’s mention of Polly being church friends with Charity back in Massachusetts is true (Cleves, Charity and Sylvia, Chapter 10).

It is also true that Achsah had good penmanship, I’ve seen it myself. Her letters can be seen in the archive at the Henry Sheldon Museum. But it’s a slight fabrication that she wrote directly to Charity. All I have evidence of is that she wrote Sylvia about Charity. (This letter is referenced in the last part of the book.)

P. 9 - The Much Anticipated and Preferable “Aunt” Charity Arrives

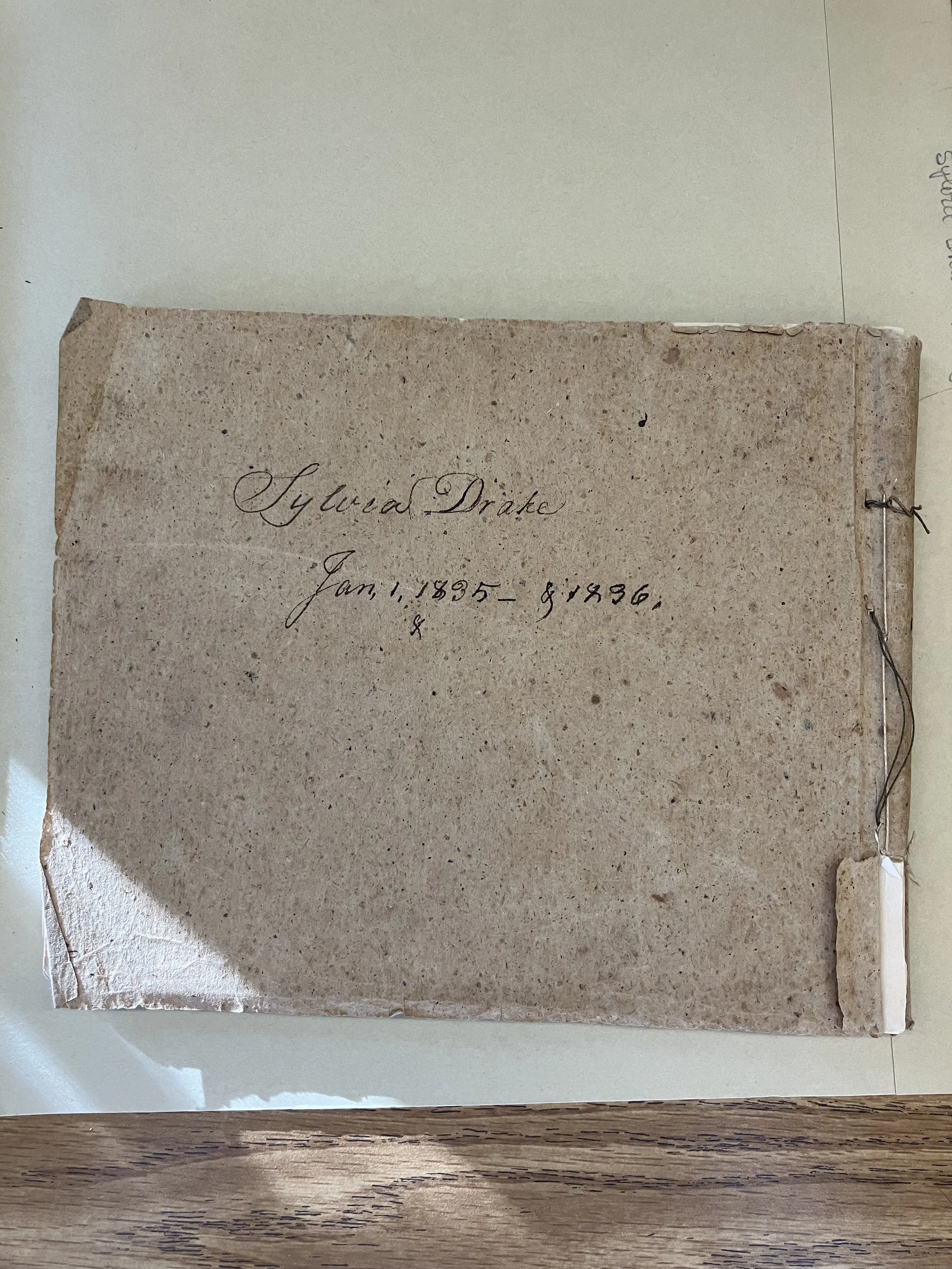

Sylvia’s religiosity, the mention of Charity’s sister Anna, and the chaos of having young children are all true. I read in Sylvia’s diary endlessly of her thoughts on faith. Here is just one example that I transcribed:

“May god permit me not to be a stranger to myself. We are brought to see ourselves vile and filthy.”

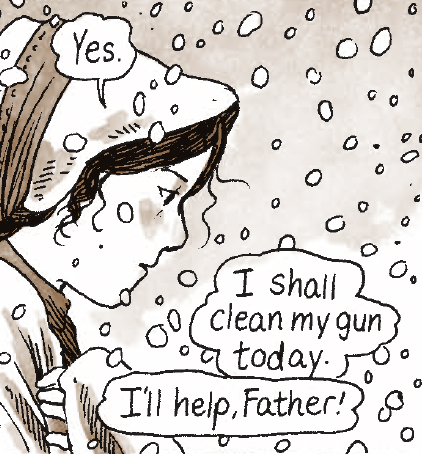

P. 10 - The Snow Will Fall, the Water Will Spill

It is true that Asaph first came to Vermont, leading the family there and away from poverty in Massachusetts (Cleves, Charity and Sylvia, chapter 2).

Cleves writes “In Weybridge, Asaph found an opportunity to escape from the condition of servitude that had confined him since age ten. After two years of work building a grist mill on Otter Creek, which ran through Weybridge, Asaph saved enough money to buy his first fifty acres of land. In another canny decision, he began courting the daughter of the mill’s owner, David Belding.”

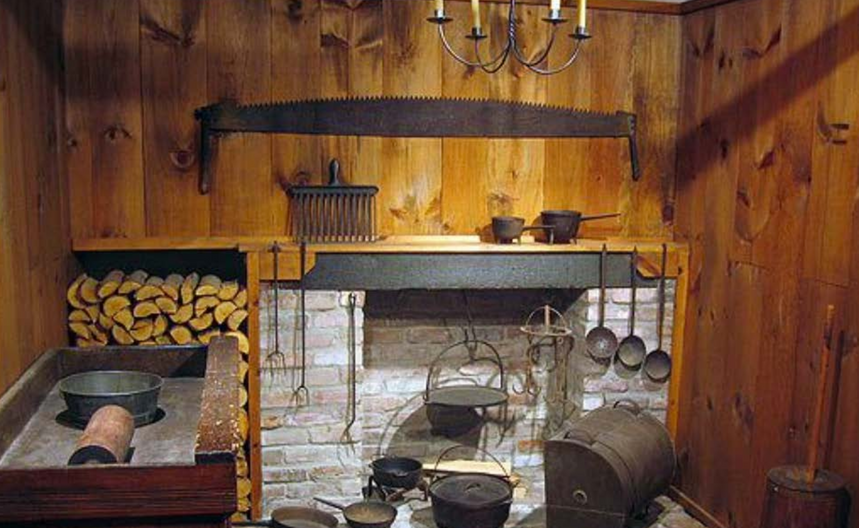

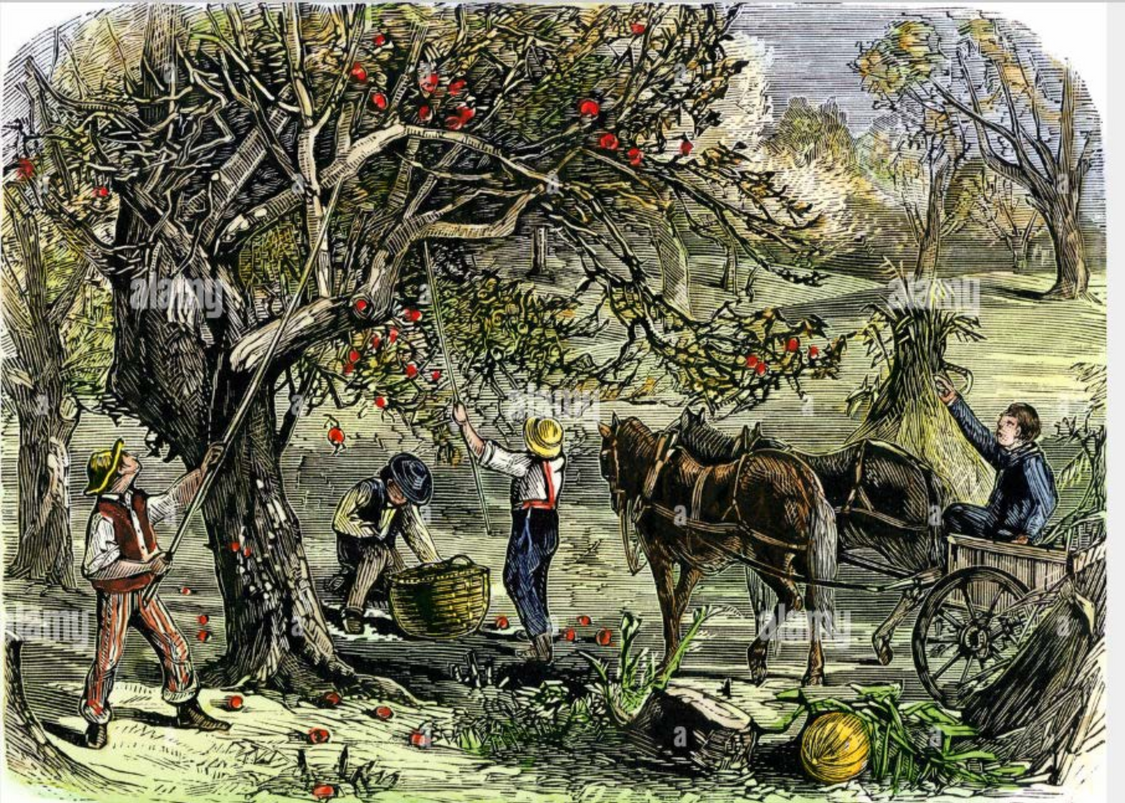

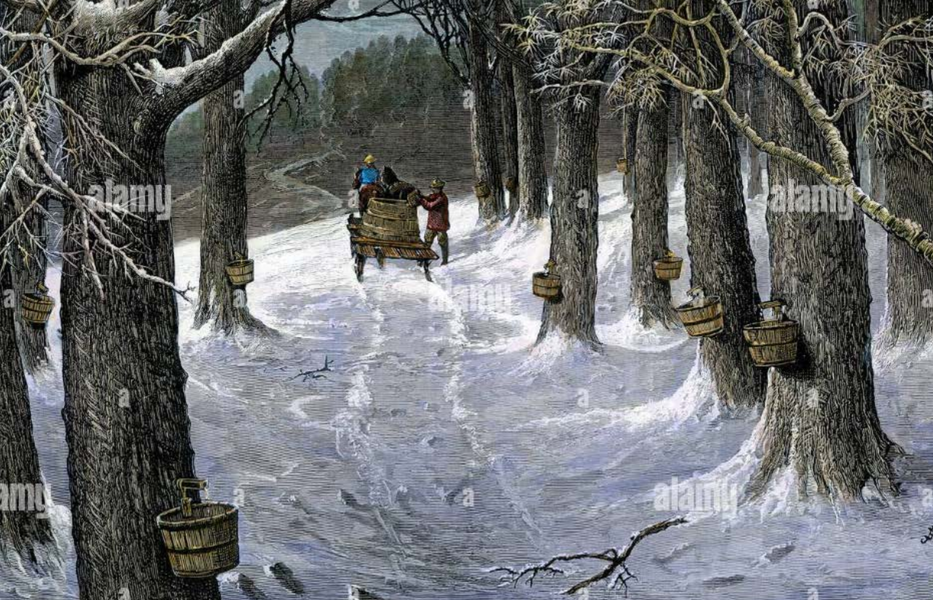

I didn’t have an exact reference for Polly and Asaph Hayward’s home and style, but below are some of the more general reference photos I used:

Summers Farm, Maryland

Log Cabin, 19th century, source unknown

Dress, Daughters of the American Revolution

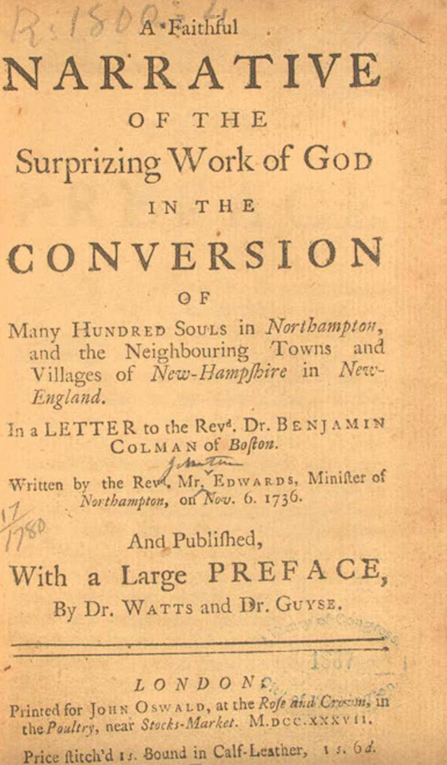

Edwards, 1737

P. 13 - Part One Title Page

I took inspiration from printed title pages from history for all of the ‘Part’ pages. I tried to emulate the spacing of the text and style of capitalization.

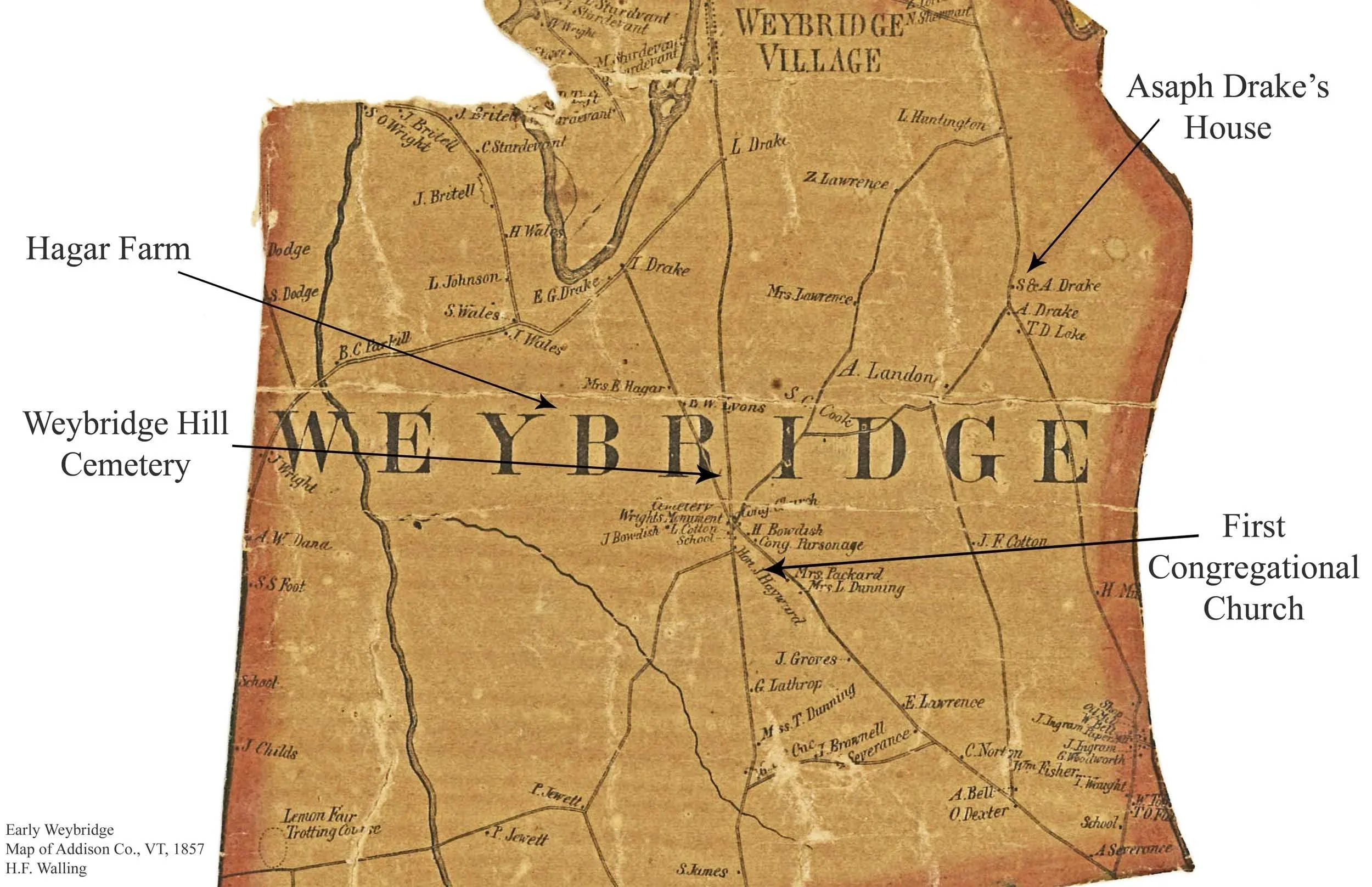

P. 15 - Map of Weybridge

This map is accurate to what Weybridge looked ca. 1800 - 1850 based on this map at the Henry Sheldon Museum. The only fabrication is the location of Polly’s house, which as mentioned earlier, was actually in Bristol, Vermont.

P. 17 - Weybridge, Oh! Weybridge!

All the imagery seen here is likely, though can’t be perfectly accurate without some sort of 1800s google street view. Based on other Vermont towns at the time, I know Weybridge was indeed a snowy place full of sheep, horses, icicles, and women in bonnets. I did have to rely on imagery from other states because my trove of Vermont imagery was limited. I prioritized images of towns and scenes in the era of Charity and Sylvia’s life.

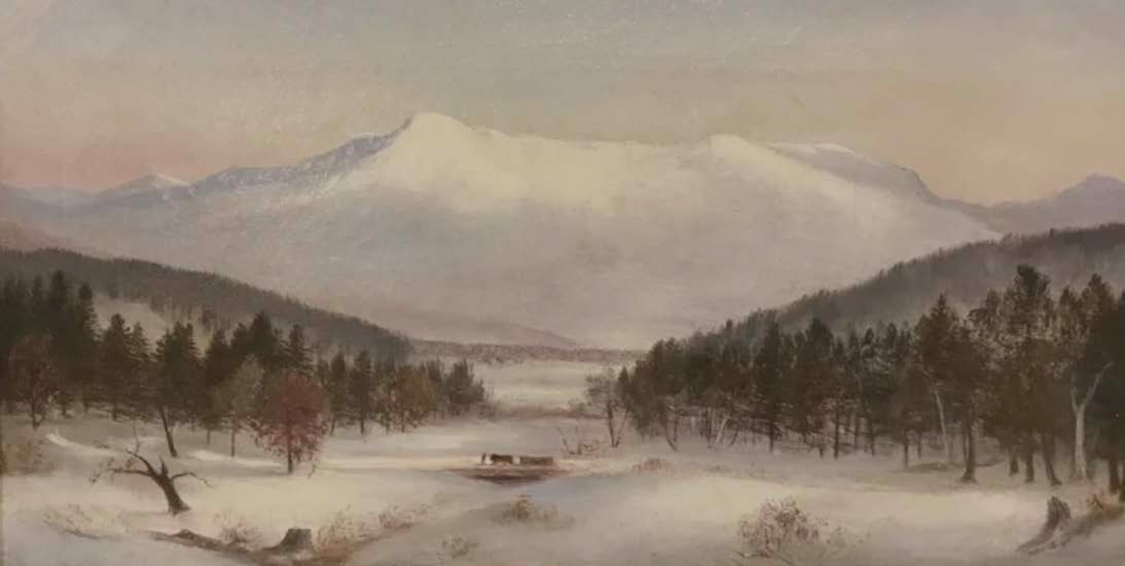

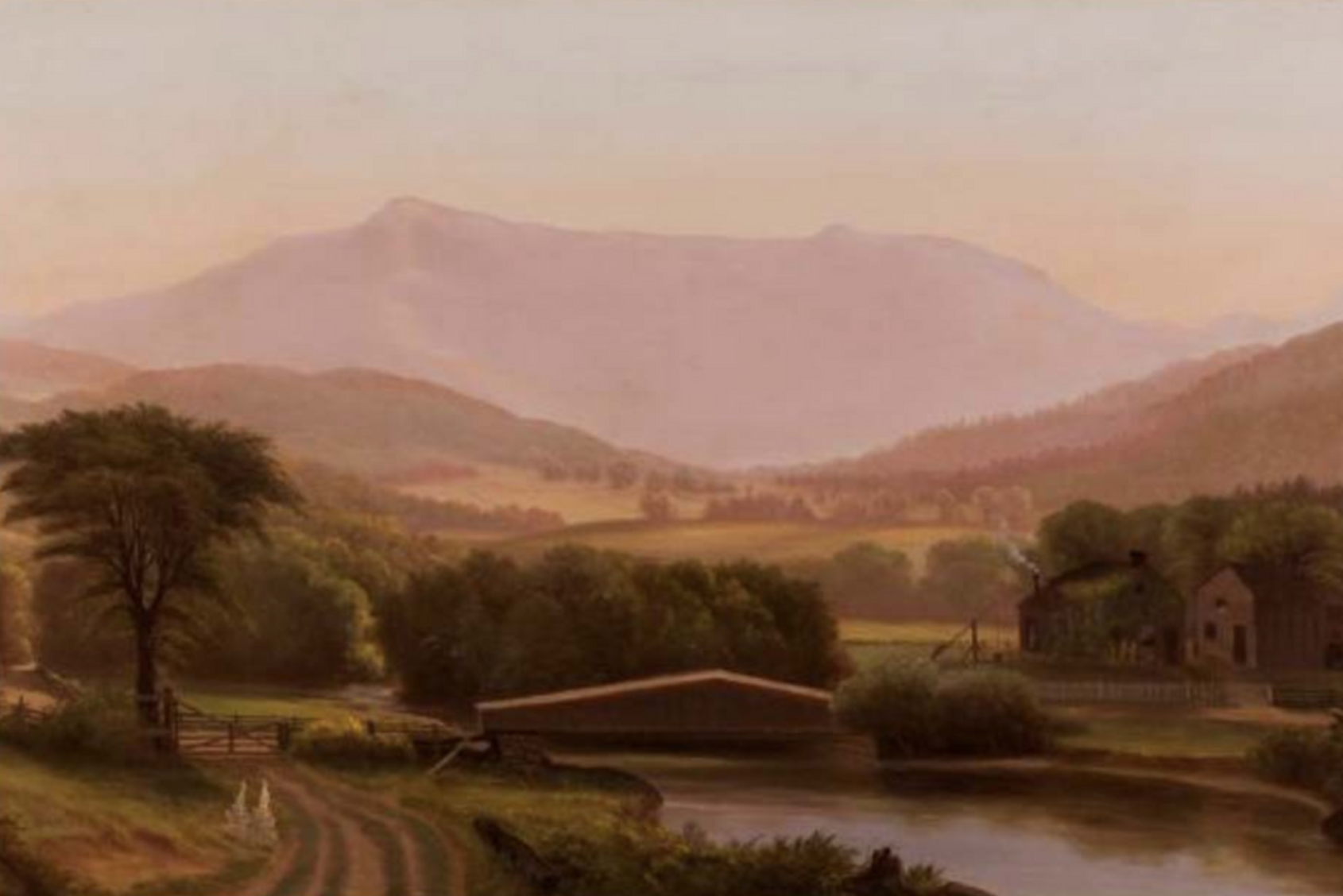

Heyde, Mount Mansfield

Massachusetts Cartoon, 1816

Iowa, Illustration, 19th century

P. 18 - To Prayer, To Meeting

Sylvia refers to going to ‘meeting’ in her journal, rather than going to ‘church. This was common phrasing in this era. It was also typical for Sylvia and Charity to attend prayer meetings on Thursday evenings at local families homes. The amount of times Sylvia mentions meeting in her journal is massive, here is a sampling from her:

“We attend the meeting, number very small.”

“The snow prevents me from attending meeting.”

“Strong south wind, walk alone to meeting.”

“Attend Thursday meeting.”

I must also note on this page an egregious continuity error on MY part. I changed how the fireplace looks at the meetinghouse on a later page, and failed to come back to THIS page and correct it to match the new design. God forgive me.

P. 19 - Praise Him, From Thy Lips

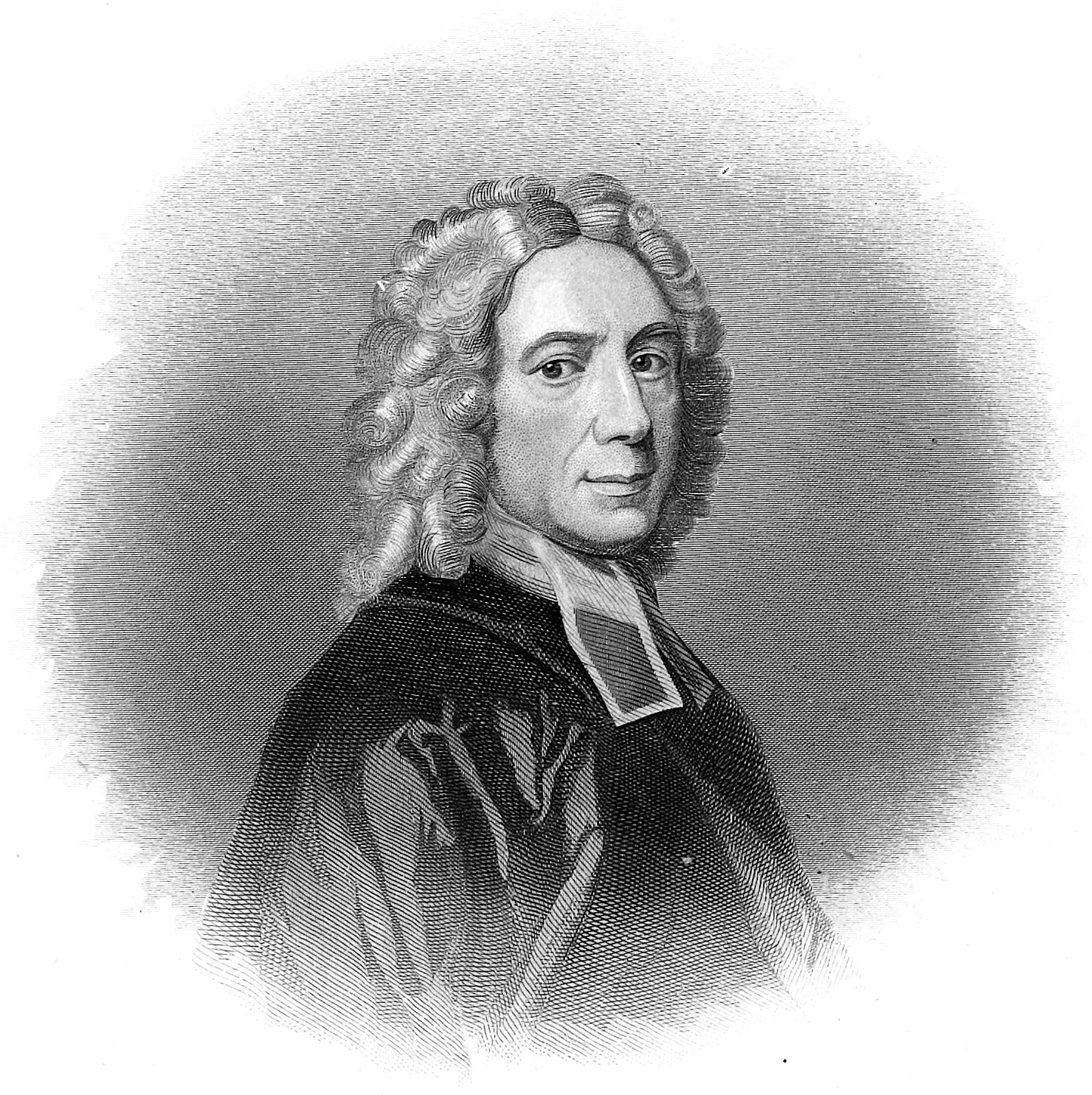

The religious verse is an Isaac Watts Psalm, a popular text in the 1800s. These refrains were often sung. Watts is referred to by some as the ‘father of English Hymnology.’ Learn more about him here.

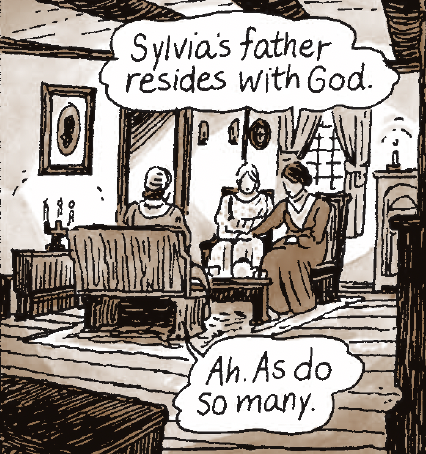

All the relations that appear here are real, but it is not known if they all attended meeting together as they lived in different towns in the area. This scene is largely fabricated in order to introduce many characters at once, and explain that Charity has left behind a bad reputation in Massachusetts. This is true, and is explained at length by Cleves in the chapter So Many Friends.

There is mention in Sylvia’s journal that her mother lived in an apartment and also mention of a home. But, there is also mention of their mother often staying with her children. I was a little confused by this - I couldn’t really figure out where her mother lived, and for how long, and so to simplify it, I imply that her Sylvia’s mother simply lives with her children for various periods of time.

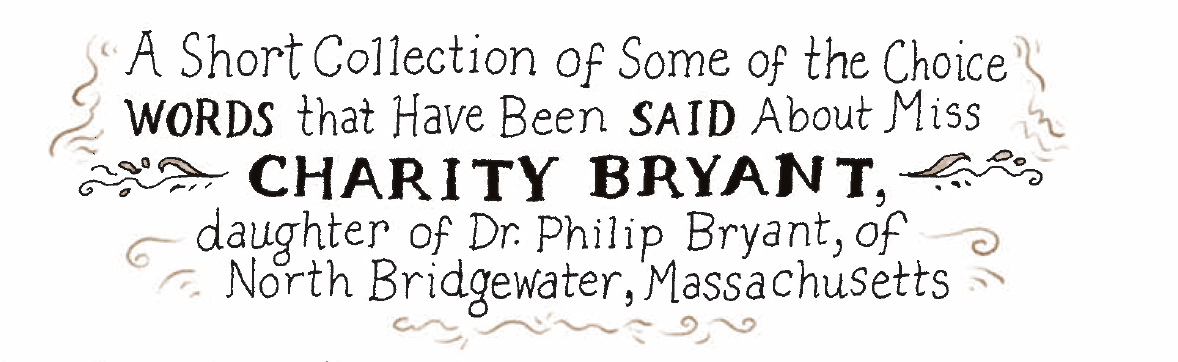

P. 21 - A Short Collection

While it is true that rumors spread about Charity, it is not known exactly what they were. These statements were formulated based upon the research done by Rachel Hope Cleves, talked about in Charity and Sylvia, Chapters 7, 8 and 9.

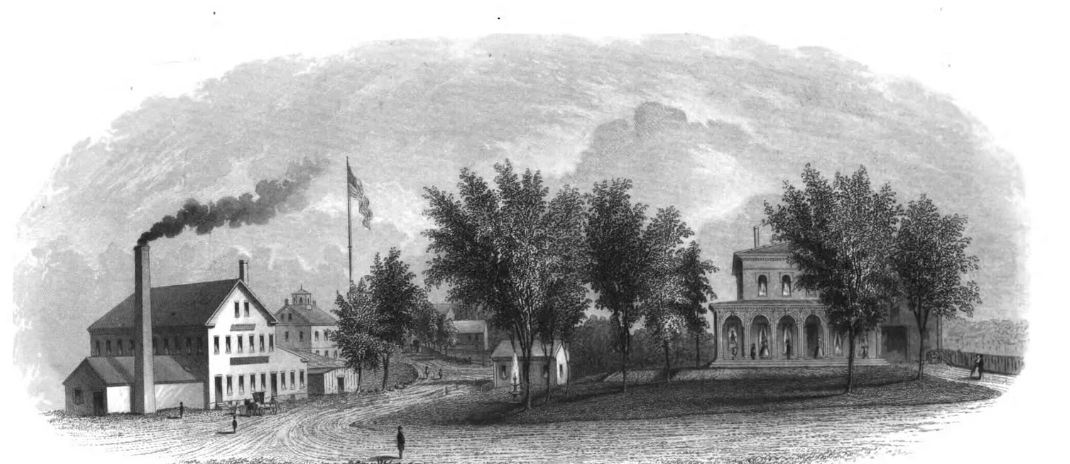

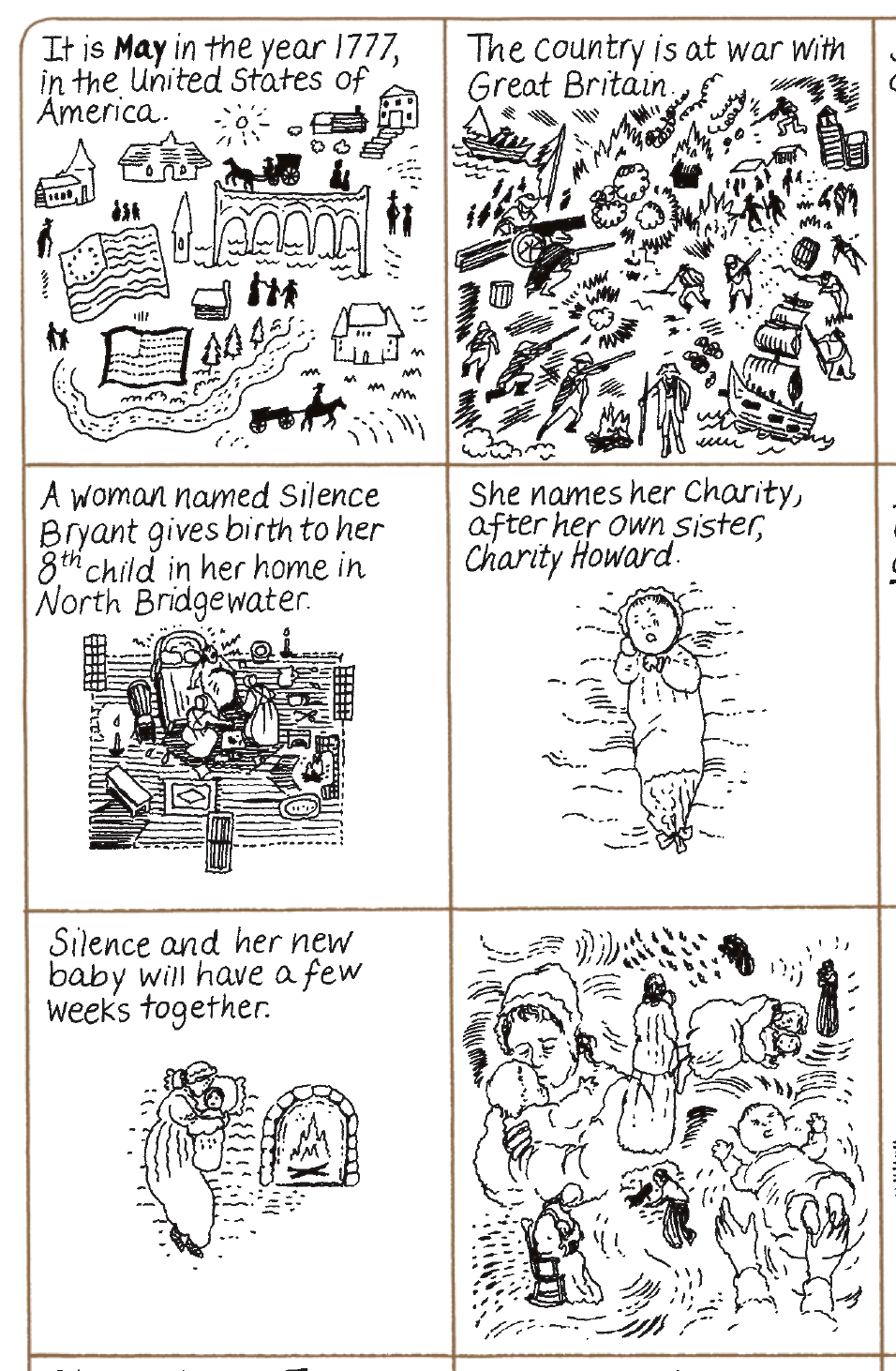

The image of North Bridewater is based upon the engraving below. Some sources indicate this is North Bridgewater, some say East Bridgewater, some say Brockton. Grain of salt, and all that.

P. 22 - In Contrast

This page was added in the second draft of the book as a way to help manage the large number of characters. I chose to focus on Polly, Asaph and Sylvia’s mother because those were the characters who were coming to life for me. The qualities mentioned are a mix of fact and fiction. Asaph’s tenaciousness is real, given how he worked tirelessly for a better life, but his ill humor is exaggerated (sorry, Asaph, I needed someone to be the butt of the jokes.)

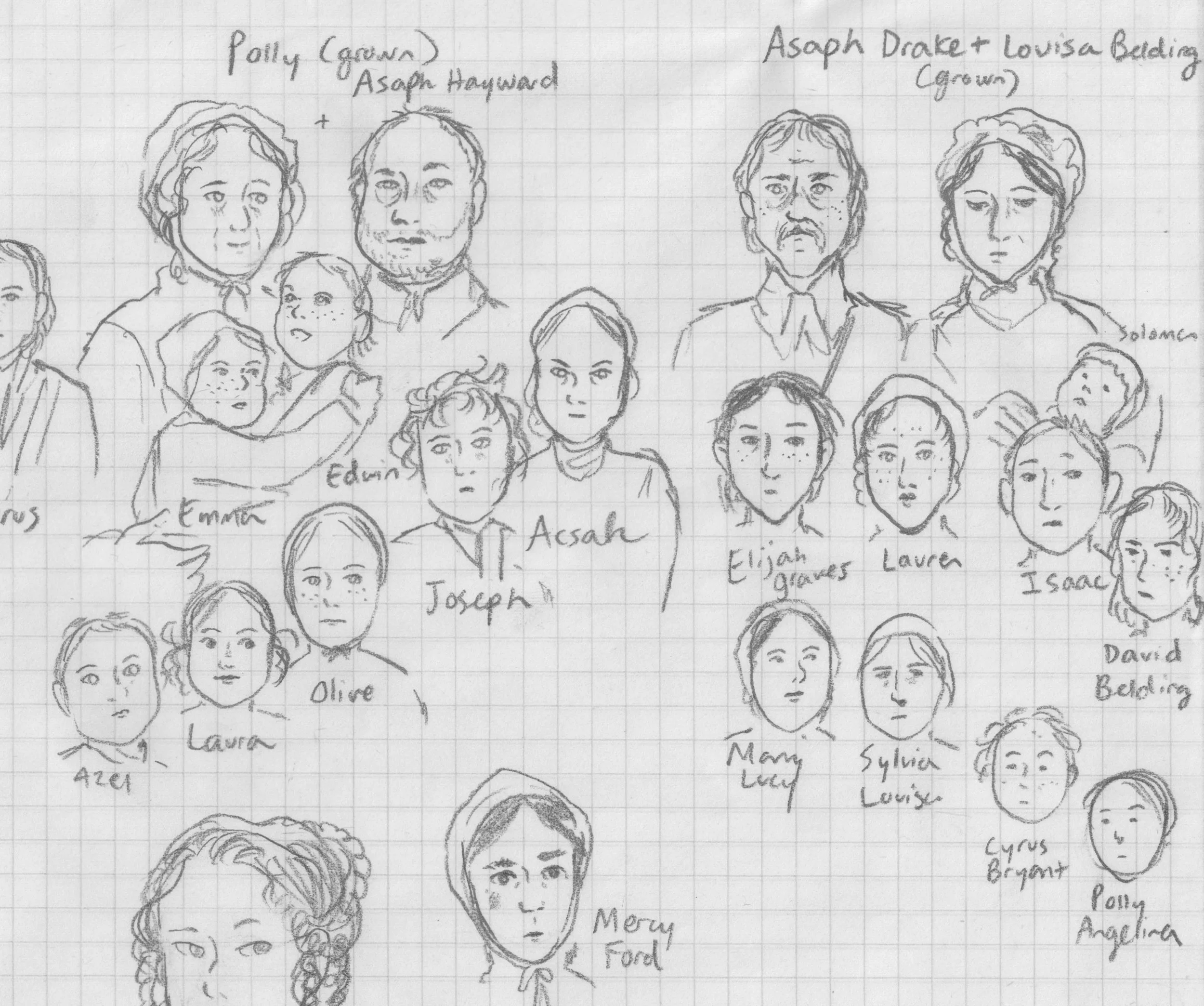

I had thought earlier on in the process that I would be drawing more of the Drake brood. It’s good I didn’t, because there’s just so many of them, but for your enjoyment here are some sketches of just two Drake families.

P. 23 - The News Will Spread

The family are speaking of the Chesapeake-Leopard affair, which happened in June 1807.

The references to shopping in Middlebury come directly from Sylvia’s journals at the Henry Sheldon Museum. She wrote:

“Go to Mdy, purchase goods to 9 dollars.”

Luckily, much bonnet reference exists. Here are some I used from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

P. 24 - The Peace of a Sleeping House

All the topics in this vignette have basis in reality. Based on Sylvia’s journal her passion for scripture was clear, and based on Charity’s poetry and letters her passion for prose was also evident.

When it comes to creating a tone of conversation that feels accurate to this time I relied on novels that Charity and Sylvia were noted to have read by Rachel Hope. Pamela by Samuel Richardson, The Coquette by Hannah Foster and Charlotte Temple by Susanna Rowson were some of my main resources. Reading a passage from any of these books will show you a similar tone to the one I inhabit:

“She had on a blue bonnet, and with a pair of lovely eyes of the same colour, has contrived to make me feel devilish odd about the heart.”

― Susanna Rowson, Charlotte Temple

P. 26 - Prayers, Quietly Whispered; Visions, Gently Seen

Sylvia often noted a sense of sinfulness in her journal. To quote her, she said she had a “heavy heart on account of my sinfullness.” At another point she writes, “Oh! Had my life been less staind with sin of the first magnitude, sin which embitter all the sweet of life.”

P. 27 - Spring Cometh, the Soil Awakens

I live in Vermont, and can confirm that the majesty of an oncoming spring is quite true. Below is the contrast of winter and spring in my driveway.

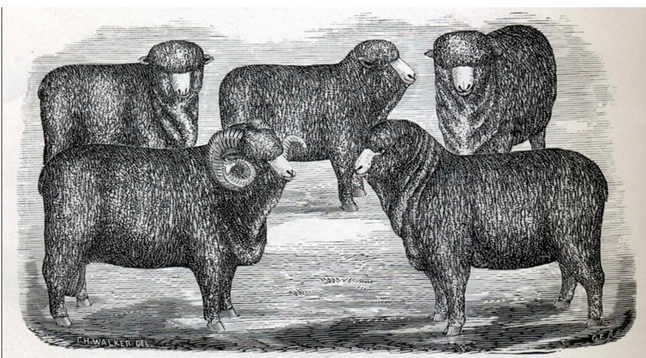

The sheep on the second page of this vignette were inspired by this illustration from the Vermont Historical Society.

P. 29 - The Previously Mentioned Middlebury, P. 30 - A Question, A Bold Question

Middlebury was bustling compared to Weybridge. In 1810 Weybridge had 750 residents, compared to Middlebury having 2,138.

Sarah Hagar was a local woman in Weybridge who was married to Benjiman Hagar. Cleves describes her situation in the chapter Their Own Dwelling. It is a fabrication to say that Benjiman Hagar was a drunk and a scoundrel, because I have no evidence of that, but it is known that Sarah Hagar’s father left land to her in her son’s names, not her husbands. Add to this that Benjiman Hagar died in Surinam on questionable business, and it paints a picture of a not-so-great husband and a woman who had some charge over her property.

There was indeed a shopkeep by the name of Dickinson, as noted on a map of Middlebury, ca. 1815 at the HSM. I was happy to include this, as one of the shows that kept me company while I drew this book was Dickinson.

Louisa did indeed have a son, and did indeed name him David Belding. Though he was born earlier than he appears in this story - he was born in 1804. I found his name extremely charming, and knew it had to be included.

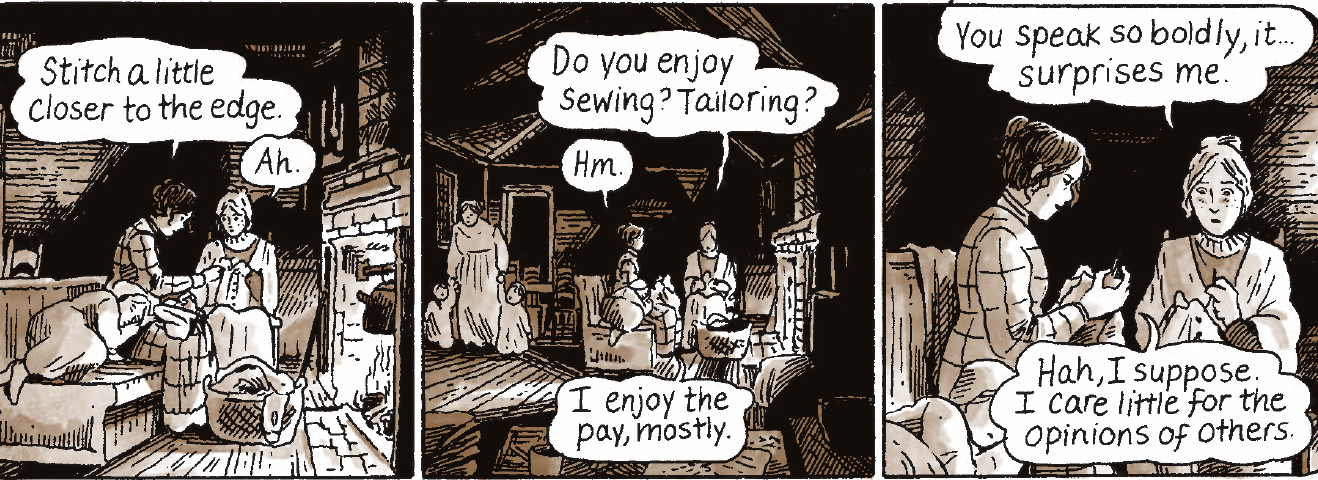

The mentioned ‘spencer’ was a common piece that Charity and Sylvia tailored, mentioned frequently in Sylvia’s journal at the HSM.

It is not known how exactly Charity came to rent a room, but according to the archivist at the HSM, the room, or possibly house, was rented in Weybridge. I chose to fabricate this section and have the room be rented in Middlebury instead. This was to narratively create a little more distance between Charity and Sylvia as they courted one another, and make their homecoming to Weybridge in later pages more significant.

Heriot, Middlebury, 1810

Hope, 1853, Shelburne Museum

P. 31 - The Washing Does Not Wait

Soap was often made at home using animal tallow, potash, and water. The amount of laundering necessary in these large families is actually hard to comprehend, but it’s not a leap to think that Sylvia was often doing it.

P. 32 - For the Cost of $1.15 A Month, A Room

I struggled to find sources giving me exact prices for goods and rent in Vermont at this time. But I got close, using this website.

P. 33 - The Rain Began Quite Suddenly

Aaron Burr was tried for treason in 1807, and this is often referred to as the ‘Burr Conspiracy.’

Sylvia mentions currants in her journal, so I know it’s a fruit they grew and ate.

I loved and relied on the fantastic youtube channel Early American to see how cooking happened in the 1800s. Almost all cooking scenes in this book were inspired by this channel.

P.34 Dinner with the Shopkeeps Brother: This is fabricated, though the concept holds some truth. I have no evidence of Sylvia’s mother forcing her to dinner with potential suitors, but I do know that in this era it would be very common for a mother to encourage and guide a daughter towards a match. Especially given the fact that Sylvia was in her early 20s, a very typical time to marry in 1800s America.

There is evidence of Polly showing concern for her unwed sister, as discussed in chapter 6 of Cleves’ Charity and Sylvia. Cleves notes that Polly told Sylvia the following in a letter:

“You are now in the bloom of youth. Now indeed is the most dangerous time of your life - you are expos’d to a thousand unseen snares. You are expos’d to the deception and the flattery of the other sex… and the impositions of the false friendship of your own [sex] - you may believe me when I tell you that there are but few real friends.”

The letter mentioned at the end was real, but I do not know for certain how Charity sent letters to Sylvia in this time. It could’ve gone through the post office, but given their proximity to each other I think it’s likely they were passed between people.

P. 35 - Hold Fast, This Night Will Not Last Forever

This scene is a fabrication. I have come across no mention of harassment in any of their papers, and there is no mention in Rachel Hope’s book. However, it seems unlikely that Charity, a woman who lived boldly outside of the norms, would go through life without any such incidence, which is why I felt comfortable with this writing. For further reading on this subject you can look towards Sharon Block’s book Rape and Sexual Power in Early America.

The details of this scene have some truth to them - Charity did have a cousin Barnabas who owned a tavern, noted by Cleves. And the phrase ‘off her chump’ was common at the time.

P.36 - A Letter to Sylvia Drake from Charity Bryant, July 2 1807

This letter is real, but the phrasing has been changed. Below is the actual text of the letter Charity Bryant wrote Sylvia Drake in July 1807, which is in the archive at the Sheldon museum:

Dear Sylvia, In haste I take my pen to address you once more, hoping it will be unnecessary to resume it again before I have the pleasure of seeing you. I am inform’d that your Brother is not going to Bristol this week and feeling very anxious to have you come this week as I have much work on my hands. I shall try to get your Brother to send a horse by Joseph to night and hope you will come as early in the day tomorrow as you can make it convenient. I thot by your last letter that you was then nearly ready to come, if that was the case. I hope by this time there is no obstacle to prevent you from being present with me before the mirdian of another day. I do not enjoy my best health at this time, but hope it is nothing more than a slight cold and the effect of my journey to Shoreham, which was rather too hard. Do not disappoint my hopes and blast my expectations. For I not only want you to come assist me, but I long to see you and enjoy your company and conversation. And tho I feel very anxious to have you come for the first consideration, yet for the last, every delay exsites anxiety in my bosom… CB.

A sample of Charity’s handwriting

P. 37 - A Few Days Pass And All the World Changes

This is a fabrication. I do not know if Louisa ever suffered from postpartum depression, but I do know that Sylvia was often helping out at their house, based on letters at the HSM and Rachel Hope’s book. As someone who personally suffered from PPD after the birth of my son, it felt like a good opportunity in the story to talk about it.

An interesting piece of history that is related: In 1890 Charlotte Perkins Gilman wrote a short story about experiencing PPD called the Yellow Wallpaper. This was an important text in the history of feminism, but like all people from history, Gilman had her complexities. Her beliefs on women’s rights were forward thinking, but she was also a racist and ultimately became a eugenicist.

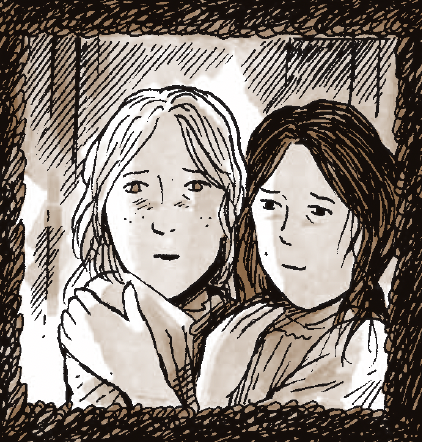

P. 38, 39 - Every Thought/Every Sensation

This is fabricated. I will sadly never know these women’s thoughts or feelings as they happened. The early years of their relationship lacked a lot of context, very little information remains of how exactly they spent this time.

The decorative border was influenced by this 1854 illustration:

Davis

P. 40 - The Room Smelled of Tallow, Sawdust and Rain

This is somewhat fabricated. Sylvia did indeed join Charity at her rented room around this time, and they went on to live their lives together. How they bonded in this moment I do not know exactly, but it is safe to say they greatly enjoyed each other’s company, to the point where they decided to form a union. Sylvia wrote in her journal a many years later, ‘Receive every attention from her who has been my companion ever since 1807.’

P. 41 - Measure, Cut, Stitch

The Jewetts were a real family in Weybridge, though I don’t know if they actually smelled of cheese. Charity’s handwriting was indeed lovely, as is evident in all the papers of hers I have had the pleasure of reading at the HSM and the Bureau County Historical Society in Illinois.

The story about Edwin being hurt by a neighbor is fabricated, but the story about Charity picking his name, and his sister’s name, is TRUE and can be read about in the archive at the HSM as well as in Cleves’ book. To quote Cleves from chapter 10: “In 1803 Polly asked Charity to be a godmother to her new twins, whom Charity named Edwin and Emma, after a poem about star-crossed lovers whose future was quashed by a cruel father.”

As usual, Charity shows she has a flare for drama and doing things differently. To name two little babies from this poem is truly odd and cool. Read the poem here!

1834 poem, Bureau County Historical Society

P.42 - How to Sup In Such a Small Room

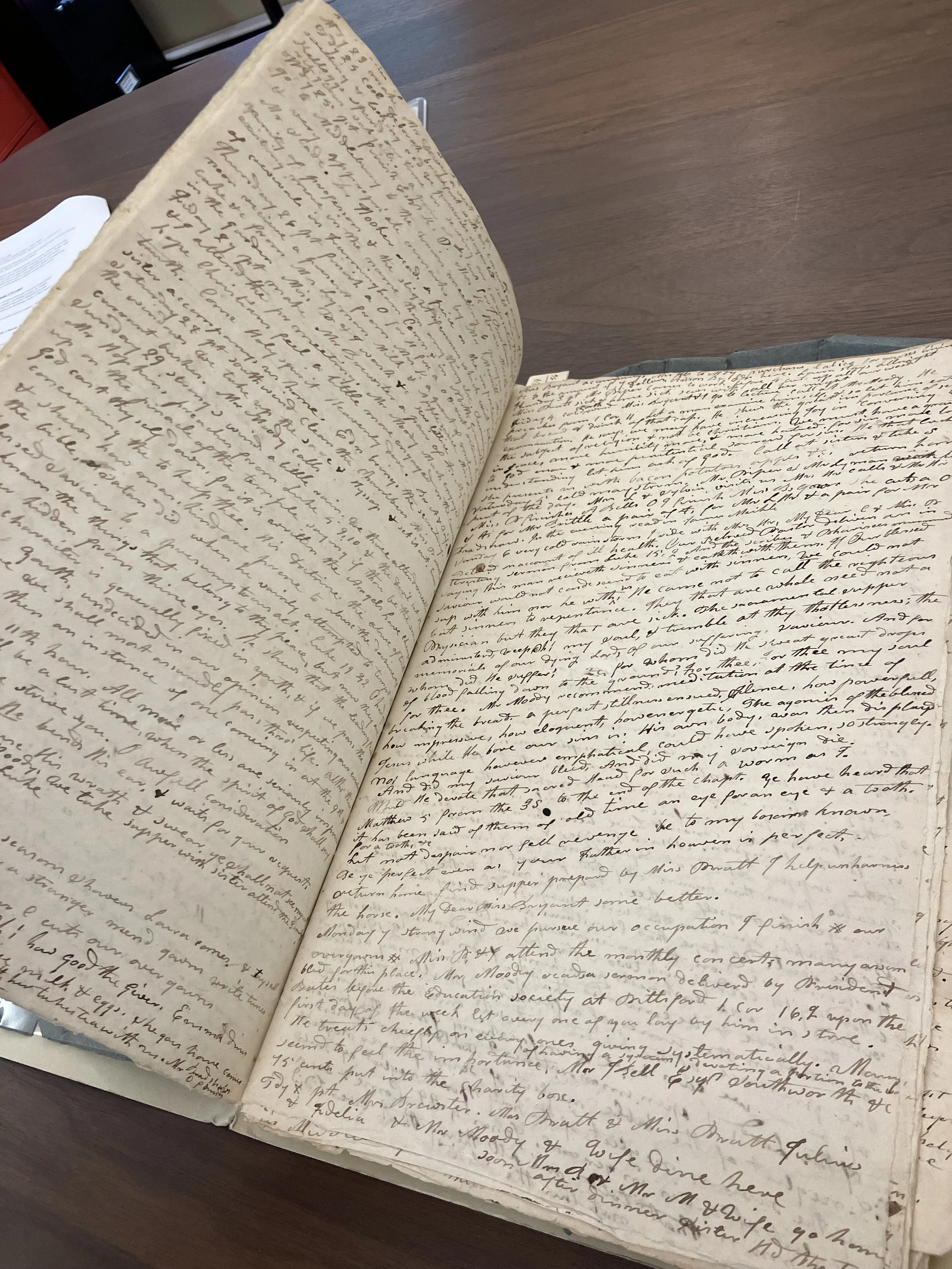

As mentioned previously, their harassment is fabricated. But Sylvia did do most of the cooking throughout their lives as evidenced by her journal, pictured here at the HSM. A few examples of her cooking prowess:

“Make bread, biscuit, applesauce”

“Move the stove, bake a turkey. Feel very unpleasantly.”

“Bake cupcake + cookey. Fill our cradle bed with feather. Ezra works for us. Chop’t and piled up by the liberality of a number of friends.”

“I pare apples, boil meat. Miss Bryant writes to Mr Lewland Howard.”

P. 43 - Yankey Doodle, A Rousing Rendition

These lyrics are true to the time. And as to the nature of Charity and Sylvia’s sexual relationship: Rachel Hope does a wonderful job expressing all the evidence of their physical dynamic throughout her book. To quote her from the preface:

“Some of the strongest evidence for the women’s sexual relationship appears in their religious writings, where they struggled with the burden of secret sings that left both women feeling uncertain about their redemption. Romantic letters hint at more positive aspects of the women’s physical relationship. In both sources, references to sexuality take the form of allusions, not direct statements. Respectable ninteenth-century women rarely wrote directly about sex of any sort, but this silence is especially characteristic of the history of same-sex intimacy.”

P. 44 - A Letter From Anna Kingman, Charity’s Elder Sister

This is quoted from a real letter, but some phrasing has been adjusted. The third panel was drawn in reference to a Heyde painting Vermont in 1850.

P. 45 - The Word, and Spelling of, G-O-D

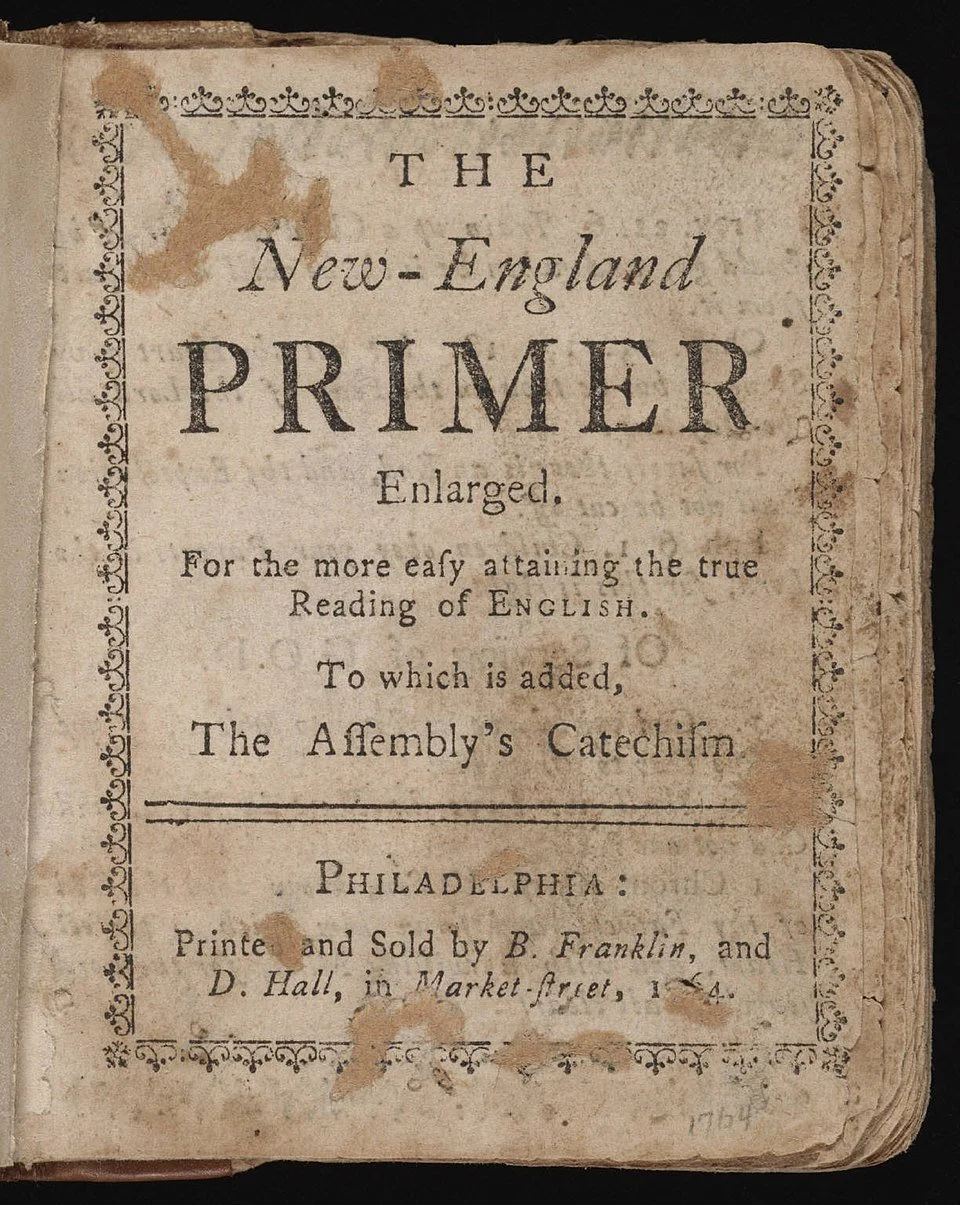

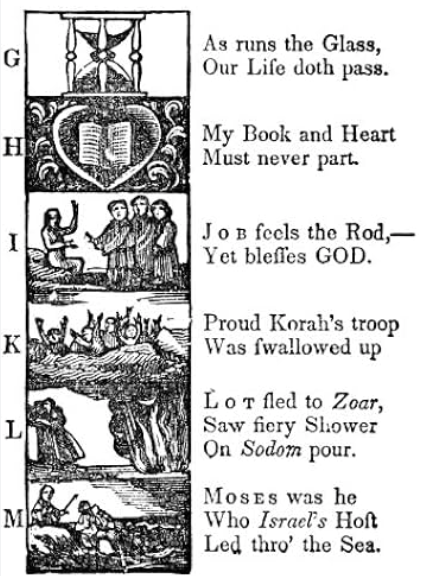

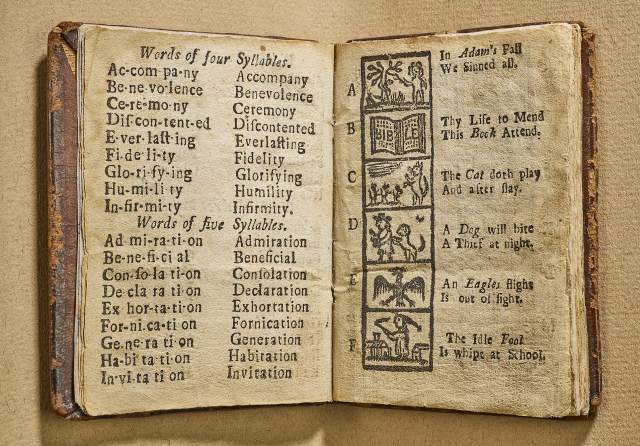

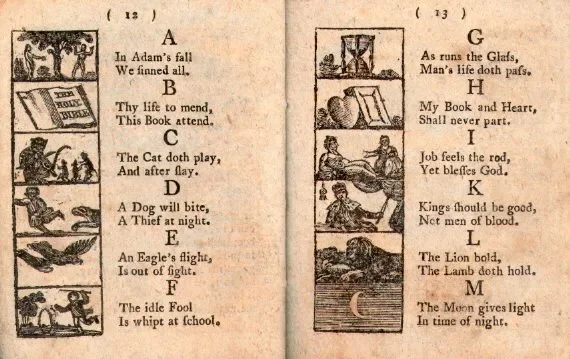

Achsah is speaking from the text of the New England Primer, the 1777 edition. The text of which can be found here, though it is also pretty easy to acquire a reprinted physical copy (which I have, and enjoy thoroughly.)

The inspiration for this vignette came when I was lazing about flipping through my copy of the primer while working on an early draft, and I noticed that all the words for counting syllables were INTENSE. The scene came to me at once.

The illustrations in the primer were also the seed of my inspiration for how part three of the book is drawn. The simplified black and white drawings with a simple line border had such a great look, and the primer itself had me thinking about their childhood. A connection was formed!

P. 47 - Life Always Changes Alongside the Seasons

Charity wrote, as described in Cleves’ book, ‘On the 3rd of July 1807 Sylvia Drake consented to be my help-meet and came to be my companion in labor.” Cleves goes on to describe, in her chapter The Tie That Binds, the power of this phrasing, and in the crossing out of ‘in labor.’ This is one piece of the ample evidence that Charity and Sylvia were dedicated to one another for life.

While this specific conversation is a fabrication, as all the dialogue largely is, it is likely that at some point in their first year of being together they discussed their future plans.

P. 48 - A More Godly Place

Sylvia says in her journal, ‘Mr C considers New England a highly favored spot on account of its religious privileges.’ which was the inspiration for this vignette. Sylvia also mentions tolls when speaking of their trips to Massachusetts. I have no evidence that they thought of the South as a barbarous, it’s conjecture on my part.

These kinds of pages are some of my favorite to draw because I have to draw very few people and get to instead focus on place and weather. Many references were used, shown here. All are illustrations from 1800s New England but the artists are unknown.

P. 49 - The Planned Route of 151 Miles

All true, and accurate to the best of my ability. To learn more about the Indigenous history in Vermont, you can look to the Vermont Historical Society, the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum, the Abenaki Nation website, as well as the book Dawnland Encounters by Colin G Calloway.

P. 50, 51 - Psalm 63, Hymn by Isaac Watts Sung in Feeling

This is again a psalm from Dr. Watts, as previously mentioned. The images of their journey are attempts at accuracy, but certainly fall short. Finding reference images for basic street scenes of ordinary neighborhoods was difficult. Something I came across constantly was that the record that exists of what people wore and where people lived was so often of the wealthy. I found many images of furniture and dress in upper class homes, but it was unusable. This was not Charity and Sylvia’s life, so I did the best with what I could find.

The pace of this vignette was inspired by the way Sylvia wrote of their journey in her journal:

“We set out for Bridgewater half past 6. Stay up all night in Dorchester at Br of Bell. Walk up 3 long hills. Call at Mr Goss in Brandon + take tea without expense.

Rest up at Natts at Pitts ford Corner. We take leave of our accommodations, pay 34 cents, call at Brooks in Clarendon, walk up 2 hills, call at Finney, Pay 10 dime, pay 17 at toll gate.

Pay 42 cents, ride as far as the greens. Heavy shower. From there to private home + dine. They shown much kindness. Build a large fire to dry us, set the table. Gate fees 34 cents. “

P. 52, 53 - Anna Kingman, Sister, Terror

My interpretation of Anna is my own. She very well could have been shy and humble, but my sense from reading her letters was that she had a similar fire in her to Charity. Below is one of Anna’s letter from the HSM, where perhaps you can glean the tone I found in her:

Tuesday —-

My dear sister! On the eve of your departure form this place, permit me to address you a few lines. — I trust it is needless to tell you how much I shall regret your absence, which takes from me so large a portion of my happiness.

Oh joys departed, never to return. How painful, the remembrance.

Yet in the hope that it will be best for you I will endeavor to find consolation, and sacrifice all selfish considerations, to the more noble principle of wishing to promote your good. I am confident, I need to under no apprehensions concerning your welfare, while so dear and faithful a friend as Miss Drake is your constant companion, and I trust you are not insensible, my dear sister, how much you are to her fidelity, and attachment. — I must now leave you, commending you to the protection of Him who is able to support and protect you thro every scene.

Anna Kingman

The other details in this vignette are true. Sylvia did indeed grow up in poverty, and her Father, at this point, was dead. All of this is detailed in chapter 2 of Cleves’ book, Infantile Days.

P. 54 - A Letter Written In Haste to Polly Hayward, Sister Of Sylvia Drake

This text of this letter is entirely fabricated, and I did so because it felt like a good moment to bring Sylvia’s voice into the story. The dialogue, however, is talking of a true crime and sham trial, that of Dominic Daley and James Halligan. It is, however, a complete guess whether or not the women knew of this trial, though it did happen in their lifetime and in Massachusetts.

Sylvia does mention in her journal of purchases made on a trip to Boston, hence the shopping sequence: “Mrs D accompany us to Boston. Purchase 3’ canton crepe shawls, 3 pairs of shews, calico for a gown, silk for one –. Pocket handkerchiefs, 2 pair of silk harp, 2 pair of waisted ones. 75’ needle. A yard of hook muslin. 10 dollars and 50 cents worth of pelise flannel.”

P. 55, 56 - The House Drown’d in Memory, Late But Oh So Welcome

All descriptions of Charity’s parents in Cleves’ book point to a strained relationship, especially with her stepmother. Hope quotes a letter that Sylvia wrote to her Mother, describing Charity’s Stepmother as someone who ‘knocks about like a house on fire.’

William Cullen Bryant was indeed their nephew, son of Peter Bryant and Sally Snell Bryant. He did actually publish a political poem as a young boy that was quite a hit. Here is the full text to his poem ‘The Embargo.’

In the original draft William was not in the story as much, but when I was reminded by Sheldon archivist Eva Garcelon-Hart of the significance of Bryant’s writing about his Aunts many years later it felt prudent to include a few more moments with him.

The house I draw in this vignette is not a direct match to the image of Charity’s childhood home in Cleves’ book. I chose instead to base their home off of this Massachusetts house because there were interior images I could work off of. And, because this world is small, the house I used as reference was coincidentally owned by a Bryant.

P. 57 - A Rendezvous With A Beloved Brother

Cleves describes Charity’s ask of Peter for a ring valued at four dollars in her chapter The Tie That Binds. Whether or not the ring was purchased and made it to them is not known, but if you’ve read the entire book you can see that I’ve decided to believe/write that the ring did in fact get to them.

Also, finally, here is a person in this story that I ACTUALLY HAVE AN IMAGE OF. The one character in this entire book that is based on a surviving portrait: Peter Bryant!

The original portrait lives at the William Cullen Bryant homestead in Cummington, Massachusetts.

The WCB homestead! I visited!

P. 58 - What Lasts Forever Always Ends

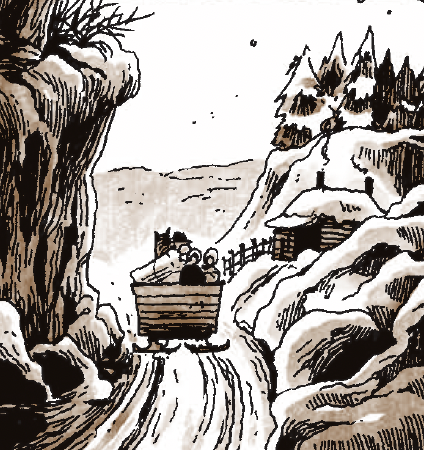

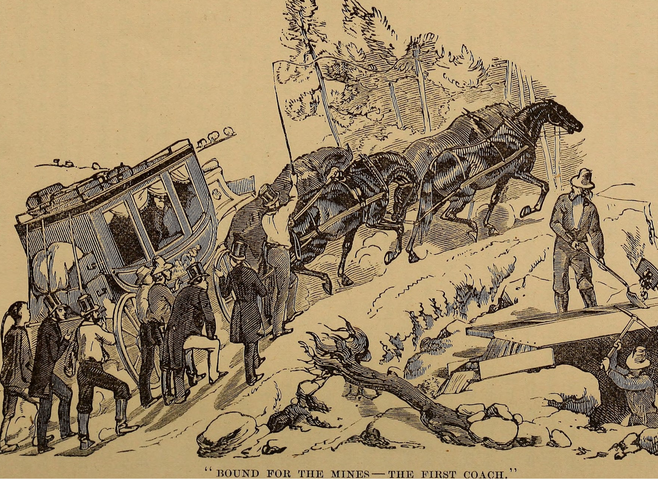

I struggled to find the amount of carriage reference I desired. Some came from the Shelburne Museum in Burlington, Vermont, some from the vast interwebs.

As to the emotion in this vignette, it is my own interpretation of the facts of their life. They did make this trip to Massachusetts, but how it felt to them is a mystery. In my own experience, growing up and returning home can be a mixture of happiness and pain, and that’s what I called upon.

1877 Strahorn

Henderson Mail Coach

P. 59 - Home, A Sensation Felt Deeply

The objects in this vignette were all seen and sketched at the Shelburne Museum in Shelburne, Vermont.

P. 60 - A Journal Entry Composed by Sylvia Drake, On A Cramped Table

These phrases are taken from different parts of Sylvia’s journal, and some are invented. Here are some quotes from Sylvia’s journal that inspired this passage:

“Return home with a pain in my head. My dear C nurses me. We have restless nights but how great + manifold are our mercies.”

“strong wind, we pursue our occupation.”

“my dear C most unwell in consequence of reading aloud.”

“Attend the funeral solemnities of Mr Benjiman Britton + his daughter Miss Anna Baird… both sleep in one grave and rest their weary head on the same earth. As the aged and those in the midst of life lodge in the cold grave together, may it remind me that my turn must soon come.”

“Purchase tea, molasses, ledticking + brandy… to the amount of 4 dollars.”

“Time rolling hastily away.”

P. 61 - A Visit to Ms. Hagar In The Heat Of Late Summer

Charity and Sylvia’s home was on Hagar land, but the details of the deal are unknown, as is the exact location of their home. Cleves writes of it in chapter 12, Their Own Dwelling.

I have driven around the roads of Weybridge wondering where exactly they lived, but no sign remains.

P. 62 - The Pudding!

The death of Ruth and Sylvia’s Father are real, the death of Asaph Hayward’s grandfather is fabricated. This vignette is here in order to talk about the prevalence of death in this era, and set up Achsah’s coming death.

P. 63 - Speak, and He Shall Hear

I do not know how Ruth’s death affected Charity, but given that they were sisters it is not too much of a reach to assume this death affected her. And Ruth, in her short life, was a writer! I have not been able to read Ruth’s writing myself, but it is described by Cleves in the chapter A Child of Melancholy.

The phrase ‘mortal career’ was used often by Sylvia in her journal.

“Mr Gervey closes his mortal career.”

Sylvia uses a myriad of other ways to describe death:

“approaching on the burden of the grave.”

“No flesh shall see God and live.”

“Inform’d of the death of Mrs Norton. She died in hope of a blessed immortality.”

“On the brink of misery and woe. Pause but a moment. See your doom.”

Gotta say, I wish I had worked ‘See your doom,’ into this book.

Serrao

Blake

P. 64 - God Heard Their Prayers

This is a fabrication to me, though the years are accurate. If you’re a Christian who believes in the power of prayer, this page can very well be true. I’m Jewish, and writing a book from the perspective of two devout Congregationalist women was at times challenging. I don’t have the background to help me deeply understand their scripture and morals. But I tried my best to understand, and have read much more of the bible than I have previously.

P. 65, P. 66, P. 67 - Uncommon, Quite Uncommon

This is a fabrication. I don’t have any evidence of the Drake’s families reaction to Sylvia and Charity living in their own house on rented land. My assumption is that it would have taken some convincing, especially since women living on their own was quite uncommon in the early 1800s. But mostly in this scene I was just having some fun. I liked the contrast of the uptight family with the escapades of young women alone at night.

P. 68 - To Build is To Love

The location of Charity and Sylvia’s house is unknown, but it was a house, as evidenced by the amount of times they refer to it as such in their letters and journals. Cleves came to the same conclusion, and references the dimensions of their home from a letter Charity wrote in 1833 to Sally Snell that is quoted later in the book. It pains me greatly that I don’t know exactly what their dwelling looked like, or what the layout of their furniture was. But I have created what I hope is something close. This article from the Vermont Historical Society on the Early House was a big help.

The exterior of their home is based on a historical home at the Shelburne Museum that I happily got to look at in person. Picture I took below!

P. 69 - It Is January 1st, 1809

This date is accurate to when they moved in to their home according to Cleves. The interior matches the inside of the house at the Shelburne Museum that was used for the exterior.